For a European audience, mention of the dictatorships that happened in Latin America in the 1970s conjures up stories of terror and torture. In this film however, this backdrop remains mostly unexplored. Neither Caetano Veloso nor Gilberto Gil, two of Brazil’s most famous musicians, who were arrested at the same time, were physically tortured. Instead, the film aims, in the directors’ words to show ‘what the experience of prison was for this great artist’. Most of the time in the film, however, Veloso seems self-absorbed, as if Narcissus is actually not ‘off-duty’ at all, and in the book, Caetano jokes that it could seem like Marcel Proust telling the story of his imprisonment!

The movie, instead, focuses on the feelings of a sensitive artist, from an admittedly comfortable background as he tries to make sense of - and also to avoid - the shock of being imprisoned. While few others are present in his telling, the political issues certainly are, with allusions to Brazil’s current political and social reality, the continuation of racial and social discrimination.

The Brazilian dictatorship began 1964. It was the first in a wave of military governments that plagued Latin America in the 70s and 80s, arguably much more brutal than the Brazilian, which was already meeting serious resistance both in the street and in Parliament from March 1968, when the March of the 100,000 took place in Rio. The response was the notorious Institutional Act 5 (AI-5), on Dec. 13th, cancelling normal democratic rights and allowing arbitrary arrest. Caetano and Gilberto Gil were arrested two weeks later.

Graham Douglas: In an interview with Variety, Caetano said that he wanted to make the film because Bolsonaro had been saying that the dictatorship was a good thing. But his experiences were not as terrible as those of many others, and the songs he sang in the film were not as strong as, for example Calice, by Chico Buarque. Do you think many people will be influenced by this film?

Roberto Calil: Since it was released, “Narciso em Ferias” has been the subject of much discussion here in Brazil. Bolsonaro’s endorsement of the dictatorship certainly makes Caetano’s vision more relevant. Yes, it’s true that Caetano’s experiences were not as terrible as those of many political prisoners during the dictatorship and Caetano is the first to admit this, but we share his belief that his story, both in the book and the film, is fundamental as a way of showing the arbitrariness, absurdity, brutality and obtuseness of the dictatorship in its persecution of Brazilian artists – in particular Caetano and Gilberto Gil.

GD: Caetano was arrested – among other reasons – because of the lies and exaggerations of the TV presenter Randal Juliano, who called on the military to arrest him. This seems very similar to the recent behaviour of Trump, but this comparison was not pointed out in the film.

RC: We wanted to make a film that was focused on Caetano’s memories and reflections on the past, a film which would transmit to the audience, what the experience of prison was for this great artist. We didn’t want to make a film full of ‘messages’ applicable to the present. But of course, we were satisfied when critics and viewers made these connections between past and present. One of these links was the fact that Caetano was arrested as a result of what we would call today ‘fake news’ – a tool much used by Trump, as you point out, and also by Bolsonaro.

GD: You didn’t intervene much during the interview. He mentioned various things that I thought would have been very interesting to hear more about. Did you make an agreement not to pursue difficult issues?

RC: No, nothing was excluded from discussion. Our approach to interviewing, inspired by the great Brazilian documentary film-maker Eduardo Coutinho, is to trust in the power of the words, gestures, and silences of the person we are talking to. This approach had even more scope in this film, in which we were only talking to one person in a minimalist scenario. The goal is to share an experience between the person being interviewed, the film-makers and the cinema audience.

In the case of “Narciso em Ferias”, the story is almost a stream of consciousness, in which he is unwinding the thread of memory, with minimal interventions from the directors. He talks about the heritage of slavery, and says that Brazil needs a second abolition, but this reflection arises from another episode - when he and the other prisoners understood that the tortures they could hear were reserved for common prisoners, not political prisoners. In the case of the sergeant from Bahia who allowed a conjugal visit, we respected his wish not to talk more about it, because of the strong feelings it evoked. We filmed over 5 hours of his statements. And, of course it’s always difficult to cut parts of a conversation. But I think that the film allowed us to make a deep and detailed immersion into Caetano’s memories. There are not many films in which one person talks for an hour and a half about just two months of their life.

GD: The story is very personal and subjective, of course, and I saw that the title was suggested to Caetano by the book, This Side of Paradise, by Scott Fitzgerald, where the protagonist, Amory is certainly a narcissistic character, and in the film, Caetano mentions that he was without a mirror for two months. Even so, I was not sure why it has this title.

RC: The simple explanation relates to the points that you mention. And that when he is able to see his reflection, at his parents’ house in Salvador, not only does he not recognize himself, but he doesn’t even understand what he is looking at. From a psycho-analytic perspective, the time he spent in prison can be thought of as a time of ego-dissolution for Caetano. Beyond this he cites “Narciso” in one of his most famous songs “Sampa”: “Narciso thought what he saw in the mirror was ugly”. The title of the film seems to me to be attractive and at the same time evocative and enigmatic.

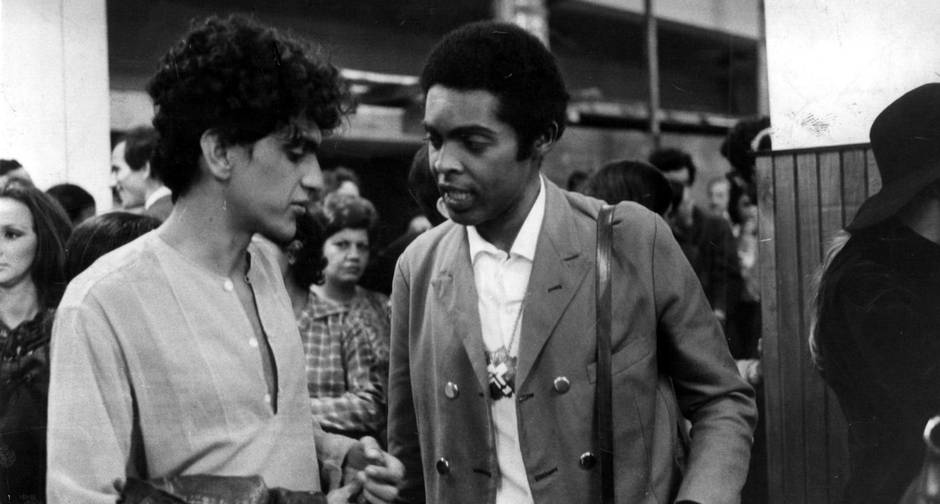

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil fled to London in exile in 1969

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil fled to London in exile in 1969

GD: Paula (the producer) wanted to make a film with a variety of scenes and locations, but once you had completed the interview you decided to stop. Why this big change of direction?

RC: In 2018 Paula invited Renato to direct the film, mainly because Caetano liked “A Night in ‘67”, a documentary we directed with him as one of the protagonists. Renato kindly extended the invitation to me, Ricardo. Caetano wanted to realize an old desire to launch the chapter from “Verdade Tropical” on his prison experience as a stand-alone booklet, and Paula thought that the prison episode also deserved an audio-visual treatment. Then in 2018 Caetano was given the dossier that the dictatorship made on his imprisonment - which had been discovered by the researcher Lucas Pedretti, and which Caetano had never seen.

But when Paula invited us, the format of the film had still not been settled. We suggested a full-length documentary, beginning with his arrest and ending with his release, and at the beginning we wanted to include the voices of other people who had been involved. But, once we had finished the interview, Renato reckoned that the most powerful film we could make on the subject -which allowed us to immerse ourselves in his memories – ought to be based simply on the material we had already filmed. We did the editing, showed the result to people whose opinions we most trusted – including the documentary film-maker João Moreira Salles (brother of Walter Salles), who is a guiding light for us in cinema, and became a co-producer of the film. And everyone agreed that this was the film. After that we showed the cut to Caetano and Paula – who liked it and agreed that the film should be the one we were proposing.

GD: The Tropicalistas were detested by many on the Brazilian Left at that time, and the military also said in the film that they saw the group as more of a threat to the established order than the traditional Left. Are Brazilian artists more left-wing today?

RC: Look, it’s difficult to talk about artists as if they were a group. There are artists of all political and ideological stripes in Brazil. Caetano has always been a very independent thinker. During the dictadura he was criticized by the Left and imprisoned by the Right. And nowadays his opinions continue to upset the right wing that has developed in recent years. He is constantly attacked by Bolsonaro supporters, including Olavo de Carvalho, the so-called guru of the president. And today Caetano is more clearly identified with the Left, through a series of progressive causes which he has recently embraced.

GD: Today, in the times of Bolsonaro, it is more difficult to raise funds for independent documentary film-making - do you have strategies for that?

RC: Bolsonaro has been continuing to destroy Brazilian cultural institutions since his first day in office. Today, the institutions that guarantee the preservation of our cinema heritage (the Cinemateca Brasileira), and the nurturing of its future (Ancine), have had their work paralysed. It is much more difficult than it used to be to make films with government support. One of the strategies to get over this problem has been investing in streaming platforms. “Narciso em Ferias” was a film funded by the producers, without government support, and then sold to the streaming platform Globoplay. This is an example of a success, but it’s an exception. The majority of Brazilian documentary film producers have suffered enormously under a government that despises culture.

Cateano Veloso performing in Almodovar's film 'Habla con Ella'

GD: You have made three documentaries about popular music – do you have a new project on the go?

RC: All three of the films we directed together – A Night in ’67, I, Carlos the Emperor and Narcissus Off-duty, dealt with popular music. Not only because it is a grand passion for both of us, but because Brazilian Popular Music (MPB) is possibly the most powerful cultural manifestation of Brazil. Caetano’s work – and that of other great composers, like Gilberto Gil, Chico Buarque and Roberto Carlos – has helped us to translate Brazil. Sometimes it has helped us to shed light on a period of darkness. At the moment we don’t have any joint projects in progress. But some of our individual ones will certainly return to the universe of Brazilian music.

The film was launched in Brazil on the streaming platform Globoplay. Produced by Paula Lavigne and João Moreira Salles