How does a boy from rural Nicaragua, a country with no history in producing either salsa stars or percussion masters, end up being both? This is the question preying on my mind as I prepare for an interview with Luis Enrique, El Principe de la salsa who became the poster boy of romantic salsa throughout the 80s and 90s with hits like Amiga, Así es la vida and Tu no le amas le temes. Just ten years ago, well into his fifties, Luis Enrique had his biggest ever hit Yo no sé mañana, which revived the salsa market and had women of all ages swooning at the now quite mature Prince of Salsa.

This wasn’t meant to happen. You weren’t supposed to be a salsa star, I point out, quite brazenly considering I’ve never met the handsome man staring at me from his house in Florida.

This gets Luis Enrique clearly animated on the other side of the computer screen.

“Actually, yes, it was destiny!” he shouts, almost leaping out of his chair. “What else could it be, when nobody would ever have dreamed of a salsa artist coming from Nicaragua? If someone had told me when I was a kid that was going to happen. I would have laughed!”

It’s true. Who would have thought? But it was not destiny, I insist.

As a small boy growing up in the remote town of Somoto in the north of Nicaragua, near the Honduran border, Luis Enrique always loved music. His uncles, Luis Enrique Mejia Godoy and Carlos Mejia Godoy were, in fact, two of the country’s best-known singer-songwriters of canción social, the songs of political idealism that were popular in the 70s as Latin America struggled against brutal regimes.

“My uncles were definitely an inspiration, but I never saw them much. They were away a lot and I lived with my maternal grandparents. I didn’t have much contact with my father’s side of the family. The greatest gift from my father’s family was the musical gene, which is very strong. They say, if you are not musical, you are not a Mejia Godoy.“

But beyond this spiritual connection, in the crazy way things turned out for Luis Enrique (which we learn about later), the famous uncles were of little practical use and had no influence on his career, which far surpassed theirs in terms of fame and fortune.

On opposite sides of the political spectrum, the two sides of Luis Enrique’s family were at logger heads. His father’s side were the ‘lefties’, outspoken against the Somoza regime that would soon be toppled by the Sandinistas after a long and gruelling civil war. His mother’s family were Somozistas and disapproving of the Mejia Godoys. But neither did Luis Enrique grow up with his mother; she was sent away by her parents, to avoid, it seemed, the perceived ‘fall from grace’ of a failed marriage to Luis Enrique’s father.

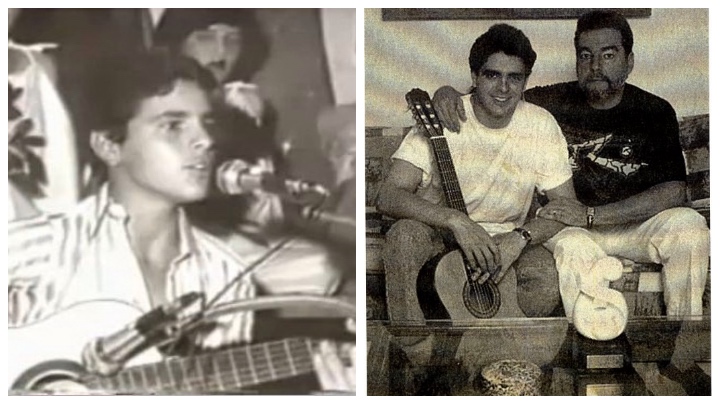

with brother Matún and with maternal grandmother

with brother Matún and with maternal grandmother

After growing up with his maternal grandparents, at the age of 15 Luis Enrique embarked on a terrifying journey through central America and Mexico, alone and undocumented, with his 13-year-old brother in tow, to cross the Mexican border and be reunited with his mother in Los Angeles.

Did he also have fame and fortune in America on his mind? I ask. He laughs at what I realise is a ridiculous idea:

“No way! Being a musician was the last thing on my mind. All I was thinking about at that moment was being reunited with my mother.“

The reunion, however, was a disaster. When the boys finally arrived in LA, she was not there and, when she did turn up, she came with an erratic lifestyle, a drug dependency and was in no condition to look after them. Alone, illegal, with no home and speaking no English, Luis Enrique and his younger brother enrolled in the local high school.

Vulnerable and surrounded by gangs and drugs, his life could have taken a very different path. “But I had a music teacher who was really kind to me, took me under his wing, and I was determined to get through school,” explains Luis Enrique, who at one point ended up living in his teacher’s driveway. “I immersed myself in music. I lived for it. It was the only stability I had.”

The Nicaraguan played the guitar and loved percussion, but he didn’t come from a family of percussionists, or even a culture of percussion, as do the best-known Latin percussionists from Cuba, Puerto Rico or Venezuela. Neither did he have the funds to attend one of the music schools to learn. So, I ask, intrigued, where did you get your confidence from?

“Confidence?” he laughs. “I don’t know about that, I guess I had a lot of energy and was kinda determined in my own way. I would go down and jam in the bars in LA and just tried to learn as much as I could. I guess I must have been driven, because I remember during High School I had a job at Wendy’s (fast food burger chain), which was very important for me because it was a secure source of food, and I felt like the happiest guy in the world; I got fed and, in my breaks, I could write music. It was all I needed.”

And this is where I attempt to debunk his myth about destiny. For, here was a boy who had crossed a continent, was alone in a foreign country with no parents. Yet he possessed the instinct to find a way through the odds stacked against him.

“I guess, looking back, I made the right decisions,” he admits. “I mean I could have ended up a drug addict, a drug dealer. That would’ve been more likely. In High School we were surrounded by that, but it wasn’t what I wanted.”

One good decision, or fate as one might call it, was to move to Miami.

“I felt that there was nothing for me in Los Angeles. So, when our salsa band had the opportunity to go to Miami, I went and I decided to stay there.”

It was in Miami, as a gigging percussionist and backing singer in different bands, where the musicians around Luis Enrique discovered that, as well as being gifted on percussion and guitar, the Nicaraguan also had a pretty good voice.

“It was never my intention to become a singer,” he insists. “I didn’t even like the sound of my own voice. I was and am a musician first.”

But others thought differently and his good looks surely didn’t hurt. When a small independent label recorded his first album as lead singer Amor de Media Noche, the boy from Somoto started to get noticed by bigger labels and Sony soon snapped him up. The label sent the salsa novice to Puerto Rico to soak up the genre and record an album; a Caribbean baptism of fire that the Central American embraced.

“They gave me a small flat and a tiny allowance. I was skint all the time, but I didn’t care, considering what I’d come from, it was a fortune!”

How was it taking salsa to Puerto Rico? I ask, thinking…for a Central American, it’s the equivalent of taking coal to Newcastle.

“I mean yeah, can you imagine?” he remembers. “It was amazing and nerve-racking!”

In his autobiography, Luis Enrique recounts his first big concert in Puerto Rico, a beach festival, in front of a massive audience of hardcore salsa fans. “I was a non-drinker, but even I drank that day, because I was so nervous,” he recounts. “In the middle of the concert. I turned my back to the audience, took my shirt off, got the sticks for the timbal and started jamming. Then I jumped on the bongos and finished with the congas.”

The crowd went wild when they saw Luis Enrique show his percussion prowess. From that moment, Puerto Rico took the Nicaraguan to its bosom and Amor y Alegría, his brilliant second album, secured Luis Enrique’s place as a salsa artist in an era of great Puerto Rican romantic salseros such as Frankie Ruiz and Eddie Santiago, and amongst the most discerning of audiences.

Needless to say, the bosses at Sony were impressed when he came back to Miami. As well as a great singer and musician, he had proved himself to be a fantastic live performer. But Luis Enrique’s personal situation was still a mess. “I was signed by a label and selling great, but I was still was illegal in the US.”

Luis Enrique finally became legal in 1989, 11 years after crossing the border, when Ronald Reagan granted amnesty to about 3 million illegal immigrants in the United States. Meanwhile his career continued to soar with a plethora of albums and hits like No te quites la ropa, Desesperado, Asi es la vida, Tu no le amas le temes, Lo que paso entre tu y yo becoming the anthems that we all fell in love with, ensuring sell out tours around Latin America.

Did you enjoy your success when it came? I ask

“Not as much as I should have done. I think I was unprepared. I learnt about betrayal, I learnt about people being around you for your money. And I still had problems with my mother.”

One of Luis Enrique’s most popular hits Date un chance directly addressed the issue of addiction, while others like Asi es la vida, about overcoming the hardships of life seemed to be directly out of his own experiences. It was very clear that, while having the looks and the appeal of a pop idol, there was something different about this pretty face of salsa romantica, though very few knew about his struggles at the time.

Luis Enrique’s lyrics, his musicianship and his stage charisma, enabled him to carve his own identity and transcend the genre in ways that other salseros romanticos like Jerry Rivera and Rey Ruiz were unable to do. Over his 35-year career Luis Enrique managed to reinvent himself many times and remain relevant as musical tastes evolved, from the sunset of romantic salsa into the dawn of reggaetón. After many years of commercial success, from 2000 Luis Enrique went through a period without recording, but he never left the stage.

“I was never afraid to do my own thing,” he explains. “People thought I was crazy when I left Sony, but the bosses at Sony had changed and I wasn’t feeling what the new people wanted. I wanted something else. I’m not sure I had a clear idea of what I wanted, but I knew what I didn’t want.”

Being unafraid to leap into the unknown has been a pattern for Luis Enrique, and one that, in the long term, has paid off. When everyone was least expecting it, out of the blue, in 2009 he made a massive comeback album Ciclos, his first number-one on the Billboard Tropical Albums chart since Una Historia Diferente in 1991. The single Yo No Sé Mañana (Who Knows Tomorrow), an apparent ode to Luis Enrique’s lifelong habit to never knowing what will come, became his biggest ever hit, with over 300 million YouTube views and a Latin Grammy, quite an achievement considering the heyday of salsa romantica had long passed.

“Do you know how that hit happened?” he asks me, as if knowing I’d like the answer he’s about to give.

“So, Jorge Luis Piloto (the great Cuban lyricist) sent me a bunch of songs and despite being great songs, I didn’t like any of them for my project. So, he sent me this one song, apologising because it was really badly recorded, you could hardly hear it. But I heard that whistle that comes at the beginning…and there was something I liked about the song. I like that one, I said. So, we were recording it in the studio, and Sergio Jorge wasn’t sure about it, wasn’t happy, was doubting. Just then, there was this guy passing by, a worker at the studio, not someone we knew, I think he was filipino, and he says to us, ‘that’s a hit.’ And he was right!”

Since then, when most of the older big hitters of Latin Music can’t resist a reggaetón collab, to appeal to the young market, it’s no surprise that Luis Enrique is, again, doing his own thing. Few thought, however, despite his huge popularity in Venezuela, that the Nicaraguan would be leaping into the complex and relatively obscure world of Venezuelan folk. In Tiempo a Tiempo, which won a Latin Grammy for best Folk album in 2020, he tackles tonadas, joropos and tamboreras, with the highly skilled Venezuelan cuatro players of C4.

Doing a joropo version of your hit Date un chance, must have been quite a challenge, I suggest…

“Oh my god! I mean, tamborera no problem I can do that (having played and recorded many times with Venezuelan band Guaco) but joropo that was something else! Super complex. After the first take, the musicians looked at me, like…I don’t know...I couldn’t find the first beat of the song, but then with a bit of help it clicked and I nailed it in the second take,” he happily remembers.

Luis Enrique’s next album, due out in 2021, is a singer-songwriting project. One senses that his veering towards a genre more reminiscent of his family influences, along with his dabbling in folk and recent songs, such as Mordaza, against what is now a Sandinista dictatorship, is taking him ever-closer to his Nicaraguan roots. He agrees, but insists:

“I am not going back to Nicaragua under the current dictatorship. It’s not about politics for me, we’ve gone from right wing dictatorship to left wing dictatorship, it’s all the same…those people have suffered so much, nothing ever changes for them.”

And so, Luis Enrique has had fame most singers could only dream of, filled stadiums, won awards…what does success look like now?

“I would be lying if I said recognition wasn’t important. But it’s still about the music, it always has been, not really the fame or anything else. I know many brilliant musicians who are not famous but very successful; they love what they do and make a good living. I do not need the fame, I just need to be making music that I love.”

Looking back, Luis Enrique has been blessed. He calls it destiny, perhaps because, for him, there never was an option to be anything other than what he is. It didn’t feel like trying. But when I think of that 15-year-old boy crossing the border, craving a mother that never materialised, it was his ability at such a young age to face fear and forge a path through pain and adversity, that carved out his destination. Overcoming each experience makes you better able to jump into the next. And the cumulative result is what destiny looks like.