Have a listen to this:

Ring any bells? Try here…

“Yo soy colombiana, oh tierra hermosa donde nací” (I am Colombian, oh beautiful land where I was born). So goes Yo me llamo cumbia (My Name is Cumbia), one of the most famous cumbia songs of all time.

Indeed: with its African drums, the indigenous gaita (a type of wind instrument) and Spanish poetic forms: cumbia is perhaps the musical genre which represents Colombia’s definingmestizaje better than any other.

Put simply, Cumbia has become the most popular music in Latin America, the only genre that has its own variations in each country. And the pan-global sampling and remixing of folkloric cumbia songs by electro DJs and hip-hop groups has caused nothing short of a revolution from Shaggy’s Euro 2008 soundtrack to sell out compilations such as Chusma Records'Cumbia Bestial.

There’s something about Cumbia

Everyone knows Shakira (though some may not realise she’s Colombian). Many will have heard of Juanes. Joe Arroyo and Grupo Niche are essentials for salsa record collectors around the globe. And if you’ve spent a lot of time in Colombia, you’ll certainly have come across Carlos Vives, or Rafael Escalona, the Vallenato legend he became famous for acting in a biographical soap opera.

But for all the global hoo-ha, it’s astounding how many foreigners who spend time in Colombia come away not even noticing cumbia. Commercial vallenato dominates the airwaves, salsa or reggaetón overwhelm the dance floors, and Colombians who want an alternative find refuge in rock and pop, national or in English. Cumbia, I was told, was music of the gamines – “street urchins”, as the dictionary translates it. In other words, the marginalised poor.

While in the rest of Latin America Cumbia also tends to be the choice of the chusma (masses), this hasn’t meant wiping it off the air waves, infact quite the opposite, as this rather hilarious clip partly demonstrates.

In Peru cumbia has developed its own independent history, from the electric-guitar based music of the 60s and 70s to the tecnocumbia of the 90s. These days in Peru, groups like Grupo Cinco play the role that commercial vallenato artists like Silvestre Dangond do in Colombia, filling clubs with cheesy, if catchy, tunes. Argentina also developed its own cumbia scene, as the music found itself fused with local styles such as tango and chamamé.

The Colombian Denial

So what happened to Colombian cumbia? It certainly had its golden age – the so-called época de oro when from when it overtook bambuco as the national music at some time during the first half of the twentieth century, to the mid-1960s when vallenato replaced it. It was towards the end of this period when the legendary Colombian record label Discos Fuentes formed Sonora Dinamita, the biggest Colombian cumbia act in history.

Yet Jamar Chess, whose New York based label Sunflower Records bought Disco Fuentes’ back catalogue, is aware of the problem: “most people don’t know that Sonora Dinamita are even Colombian. It’s the Mexican community that love Sonora, and many of them think they’re Mexican. Cumbia is not known as a Colombian genre, loads of people in Mexico and the States probably think it’s Mexican.”

And as Chess, himself the heir to the legendary US Blues label (Chess Records) that discovered Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry, admits that even Discos Fuentes is more famous for salsa than it is for cumbia. However, the story goes a lot deeper.

“Music of the slaves”

The West African rhythms which characterise cumbia and other Caribbean music arrived in Colombia via the port of Cartagena de Indias, the centre of the slave-trade in the Americas. For DJ José Luis, this is an important factor in the lack of acceptance of and appreciation for cumbia among Colombian society.

“Cumbia has always been slightly looked down upon by many sectors of the Colombian population,” he said. “This is probably because it is traditionally the music of black people. It is said cumbia is danced in the way it is because that was the only way slaves were able to dance with a ball and chain weighing down their ankles. It is a legacy that lives on.

“You have to remember the rather static nature of Colombian society, which remains very Catholic and traditional. It has not, for the most part, been possible to reverse Cumbia’s connotations as being lower-class music, or the music of the slaves.”

In other words, that Cumbia characterises mestizaje – the range of racial and cultural facets which makes up Colombian society – is not necessarily an asset if you’re looking for widespread acceptance, especially when the black element is so prominent.

Cumbia originated with the folkloric gaitero music – now being spread across the globe thanks to Los gaiteros de San Jacinto ( – which combined the African drums with the indigenous gaita and maraca. Words – the Spanish element – were the final piece in the puzzle, a late edition as cumbia evolved. Even so, the lyrics can still seem secondary. Steen Thorsson, compiler of Cumbia bestial one of the modern electro-cumbia records mentioned earlier, sums it up: “Cumbia is above all a rhythm, a dance.”

Cumbia’s need for an ‘Escalona’ figure

For José Luis, this was also an important factor in Vallenato’s takeover of the mantle from cumbia. “With Vallenato, the key is with the lyrics,” he said. “These songs have been taken by Merengue artists and Bachata artists – the words are what matters. Rafael Escalona for example, may have been a humble man but he was very sophisticated as a composer. This took Vallenato to the middle-class in a way that the rawness of Cumbia was unable to achieve.”

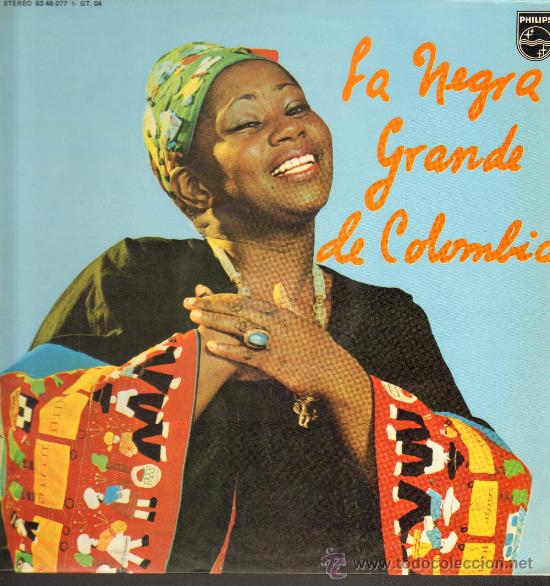

Indeed, when asked for the Rafael Escalona of Cumbia, you would be hard-pushed to find an equivalent. Escalona brought Vallenato from the remote coastal Guajira region and turned into the most recognisable style of the entire nation. “There has not been a talismanic figure for Cumbia in the way that there has Vallenato,” says José Luis. “Shakira touched on Cumbia a bit, but even artists who incorporate more cumbia into their albums – such as Toto la Momposina (who recently played in the UK) – are not that well-known in Colombia. There are plenty of people who do not know who she is.”

There was one final obstacle in Cumbia’s way: the stranglehold traditionally held on Colombian radio by payola – the illegal practice by which record companies pay to have their songs on the airwaves, thus leading to a monopoly held by mainstream musical establishment. If Cumbia wasn’t in vogue with record label bosses, no one was going to hear it. As Thorsson, also known as DJ Tío Changó, says, “for a very long time Cumbia was ignored by the country´s white elite as efforts were made to keep it away from radio stations and concert halls. They have always tried to marginalise this music. In schools is Bogotá you learn about European music, classical music.“

The Secret in the Beat

So how has it survived? Moreover, how did it manage to keep expanding? The response is unanimous.

“The rhythm. It’s intoxicating,” says José Luis. “You can’t escape it.”

“It has a groove which is incredibly made for dancing,” says Thorsson. “For me it’s because of its offbeat. The rhythm sort of gets inside people. It’s like a very danceable reggae.”

And this beat is the drive behind its popularity with urban music producers, too. “It’s so catchy, and the tempo especially makes it suited to samples,” says Dorance Lorza, leader of top UK Latin jazz band Sexteto Café.

“At the end of the day, they’re great songs,” says Jamar Chess. “That’s what counts.”

Our question still remains partially unanswered, though: how did this marginalised style make the journey from the docks of Cartagena to the decks in DJ booths? According to José Luis, an 80s Italian pop singer with the pseudonym of Gary Low (http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Low), rather surreally, played a major role.

His version of Peruvian composer Walter León’s classic La colegiala, originally made famous by the Colombian Rodolfo Aicardi was notable for more than just the Italian’s being the first man (probably) to ever beat-box to cumbia.

“In terms of making a pop song from Cumbia, this was absolutely massive”, said José Luis. The release was a big success in Spain.

Even so, it is a long journey from Gary Low’s 80s mullet and horrendous taste in clothes to where cumbia is now. Mixes are prolific, varied, and from across the globe.

Ibiza-bound

Before Shaggy took Cumbia cienaguera to Euro 2008, it had in fact already been sampled by Swiss-Iranian producer Samim. Heater was a massive summer hit in 2007, spectacularly signifying cumbia’s arrival on the European dance scene and taking a Colombian folk classic to the dance floors of Ibiza in the process. Soon followed Michel Cleis’ remix of Toto La Momposina’s El pescador and a phenomenon had been born.

As licenser of Discos Fuentes’s back catalogue, Jamar Chess finds himself with a heavy workload. “It has only been recent, in the last couple of years, but the volume of requests I have had from producers and DJs has been staggering,” he said. “There has been great interest across Europe: France, Spain, Italy and the UK are showing the strongest interest, but in the US too. A few Brooklyn hipsters asked me to send them some stuff the other day.”

Chess has sent a lot of Discos Fuentes’ records to Gigi De Martino, an Italian DJ whose reworking of Sonora Dinamita’s classic Mar adentro made it to number 4 in the Italian dance charts.

There are also hopes, according to Chess, that recent interest will spark a revival for cumbia music in its more traditional form. “Often the best thing about these rehashes is that they point audiences towards the original,” he said. “For a number of the people sampling it, it’s an entirely new sound – it’s quite niche.”

Indeed, Demon Music in the UK have recently compiled The Beginner’s Guide to Cumbia,(http://www.demonmusicgroup.co.uk/Product.aspx?ProductID=5125#TL) with one disc named “future cumbia” and including the likes of Bomba Estéreo, the Bogotá-based hip-hop fusion group.

A Movement from the South

The mention of Bomba Estéreo should alert to us to one indispensable fact. Although big-name European DJs may be filling dance floors, this is a movement driven by Latinos themselves. Moreover, in keeping with the history of cumbia, it is intrinsically linked to the socio-political.

Steen Thorsson, or DJ Tío Changó, himself half-German half-Chilean, commented on the importance of the Latin diaspora. “On one hand, you have to remember the number of Latino immigrants there are in the world – in all social circumstances,” he said. “And remember that this immigration is almost always an urban process, and that Latinos are seeing music all over the world being urbanised.

“But this is also happening in Latin America, and especially in Colombia, where the cities are unrecognisably large compared with how they were ten or fifteen years ago. People are coming from rural or coastal areas to Bogotá and other cities, and bringing with them cumbia rhythms. There have been similar processes with other Latin genres across the continent, so cumbia has taken momentum from them.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising, therefore, that the two key figures in the movement Thorsson highlights live in Monterrey, Mexico – where cumbia took off like never in Colombia, and the stepping stone between Colombia and the United States.

One is Celso Piña, twice nominated for a Latin Grammy. Meanwhile, Toy Selectah mixes for Control Machete, Latin hip-hCop pioneers and counts such names has Morrissey, Calle 13, Eminem and Manu Chao among his list of collaborator. “These guys were fundamental. They led the way in mixing cumbia with certain rhythms,” says Thorsson.

Cumbia bestial, the title of Thorsson’s cumbia compilation and the DJ’s name for what he calls the “bastard style” that is emerging from the cumbia scene, duly presents mainly Latino artists – but takes them from as far from Bogotá as Melbourne, Berlin and Texas.

To the Heart of Cumbia

Ultimately, therefore, cumbia has still not been able to separate itself from its social circumstances. Yet were it to do so it would surely deny an integral part of what cumbia music means. As Thorsson remarks: “Cumbia is a music with a rich history, that is embroidered in the stories of so many people, people of live from its rhythm, from the happiness it expresses.”

“Musically, culturally and politically, Colombia is not one country. It is many countries,” said Thorsson. “There is more difference between Cali and the Caribbean than there is between Switzerland and Poland, for example.

“We are now seeing a fascinating process. People are being drawn towards music that goes beyond cumbia, because cumbia itself evolved from other traditions. There is growing interest in porros, gaitero music, all that lays behind cumbia. People are catching onto that old, authentic music, learning about the history that engulfs it.”

Most importantly, electro cumbia has the potential to reach far beyond giving a good night to the drugged-up crowd in an Ibiza club. It could possibly rediscover, for many people, the history of a marginalised culture – that of the Afro and indigenous peoples so often made invisible in Colombia.

Finally, if you were traumatised by Gary Low’s appearance earlier on the article, try this one for size, and reflect on how far the cumbia has come: Copia doble son sistema with Colegiala