Cuando sepas que he muerto no pronuncies mi nombre

porque se detendría la muerte y el reposo.

[When you learn that I’ve died don’t speak my name

because then death and peace would have to wait. …]

In this poem’s reference to death, we sense the danger Roque Dalton faced as an urban guerrilla fighting for revolutionary change. Early death to Dalton was not merely a romantic trope, a sign of youthful angst. It was a possibility that he and thousands of other Latin Americans of his generation faced in their efforts to mobilise against the dictatorships that had settled on their countries like a black shadow. And in the poem’s plea for silence, we see a stoic reminder of his years spent living underground, in the clandestine world of guerrilla cells, in which discretion was of utmost importance.

This selection of poems by Roque Dalton is the first time his poems have been published in the UK and this bi-lingual edition is an excellent introduction to the work of this great Central American poet. Superbly translated by Michal Boncza and John Green, the poems can be appreciated by those with knowledge of the Spanish language as well as those without.

Roque Dalton was born in San Salvador on May 14, 1935, the illegitimate son of a Salvadoran nurse and a wealthy American sugar planter. He was raised in a working-class neighbourhood by his mother, who also ran a popular variety store where young Roque learned the popular, slang-laden language that later found its way into his writing. He attended a day school for the elite, the Jesuit-run Externado San José, paid for by his father. His life thus began with a series of acute contradictions, raised as he was in a poor neighbourhood yet schooled amongst the elite, disowned by his father yet subsidised by him.

These ironies gave Dalton a sharp eye for the absurdity and hypocrisy of El Salvador’s conservative order, which he spent his literary career holding up to ridicule and, later, sought to overturn with revolution.

His political education began in Chile, where, in 1953, he went to study law. In Santiago he met the exiled Salvadoran union organiser (and future guerrilla commander) Schafik Handal and, in a brief but important encounter, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. His travelogues from those years are full of life and humour. Shortly after Dalton returned to El Salvador, the reformist government of President Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala was overthrown in a CIA coup.

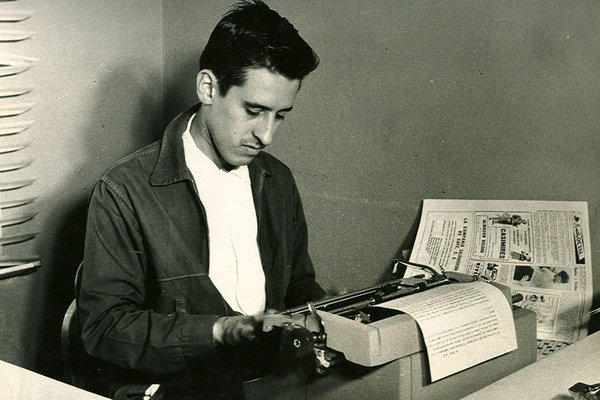

Arbenz supporters streamed over the border into El Salvador, among them a young poet and journalist carrying a typewriter, Otto René Castillo. He and Dalton became close friends and collaborators. Dalton’s first important book, La ventana en el rostro (The Window on the Face), published in Mexico in 1961, was a slim volume of melancholy love poems and hymns written under the influence of Neruda. His work took a harder edge with his next book, El turno del ofendido (The Offended Party’s Turn), which, in an example of Dalton’s provocative wit, was dedicated to the police chief responsible for his detention for illicit political activities in 1960. That detention might well have ended with Dalton’s execution – many never made it out alive – but instead the military government was overthrown in a palace coup and Dalton was released with hundreds of other political prisoners.

In 1964, he was arrested again in San Salvador and this time had an even more improbable escape. While Dalton was in detention, an American CIA agent tried to recruit him. Dalton refused and was sent back to his cell, where, a few days later, he escaped by pushing through an adobe wall. This incident – recounted by Dalton in a posthumously published novel and confirmed much later in its basic outlines by declassified CIA documents – helped give him a reputation for miraculous saves and derring-do.

Dalton moved to Czechoslovakia in 1965, working for the Spanish-language edition of World Marxist Review. His essays for that now-gone magazine are mostly uninspired hack work, but his three years in Prague proved to be the most stable and productive of his career. After years on the run from police in San Salvador, Dalton and his wife Aída Cañas and their three sons could finally live in peace. He wrote Miguel Mármol, an account of the 1932 massacre based on his interviews with the communist organiser and survivor of the title, and a seminal text in the Latin American testimonial genre.

In their modest Prague flat, he wrote his mostly critically acclaimed book Taberna y otros lugares (Tavern and Other Places), a blindingly original and self-confident volume of poetry, prose poems and theatrical dialogues. Taberna has a clarity of voice and thematic range never equaled in Dalton’s career or arguably in the whole of Salvadoran literature. The title poem is a long collection of dialogues and snippets of conversation overheard at the tavern U Fleku, with voices that seem to rise and fall on the page but with an undercurrent of anxiety that reflected Prague’s climate in the months before the 1968 armed intervention by Warsaw Pact troops.

Dalton left Prague just weeks before Soviet tanks rolled in. Numerous people have described his dismay at the demolition of the ‘Prague Spring’ but he never made his feelings public. He headed to Cuba where he lived until 1973, a period in which his reputation soared. Taberna won Latin America’s top literary prize, the Casa de las Americas, in 1969. At a time of shortages and uncertainty, Dalton’s charming presence seemed to be everywhere: writing and producing a Brecht-inspired play with playwright Nina Serrano for Cuban television, writing essays for Casa de las Americas and Pensamiento Crítico magazines, holding forth at cultural forums. He wrote perhaps his most Salvadoran book, Las historias prohibidas del pulgarcito (The Banned Stories of Thumbelina), a collage of poems, anecdotes and news cuttings that showed the influence of his friend Eduardo Galeano. That book, its title taken from Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral’s patronising reference to El Salvador as “Thumbelina of the Americas”, included the famous “Poema de amor” (Love Poem), a warm-hearted paean to Salvadoran workers.

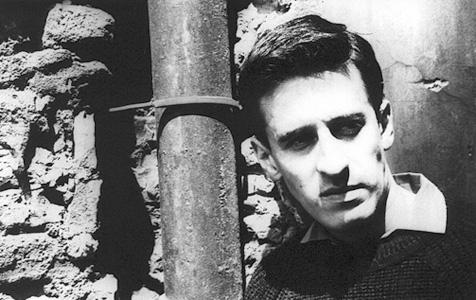

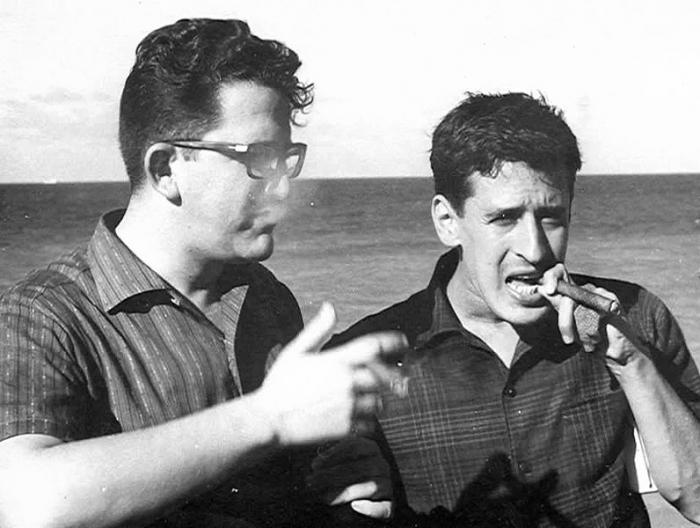

Roque Dalton with Heberto Padilla in Havana

Roque Dalton with Heberto Padilla in Havana

Yet Dalton’s time in Cuba soon took a dark turn. He had a bitter falling out with the leadership of Casa de las Americas that stemmed in part from his excessive drinking. He saw several close friends lose their jobs or official favour during the revolution’s early 1970s hardening. Friends in Havana said they lost all trace of him. They learned later he was completing an intensive guerrilla training course in preparation for his return to El Salvador. He underwent plastic surgery to alter his appearance as he was, despite years in exile, still a public figure in his home country. Many people seem to have had reservations about whether Dalton, inveterate drinker and bohemian now in his late thirties, was suited to guerrilla life. But he insisted and so he went.

Dalton arrived in San Salvador in December 1973 for what turned out to be a disastrous spell with a relatively new organisation called the People’s Revolutionary Army. Hard-liners were in ascendancy. Some in their late teens and twenties, they knew or cared little about Dalton’s career as a poet and saw him instead as an undisciplined drag, a charge strengthened by the fact that he had an affair with a commander’s girlfriend. He turned out one more book, a volume of poems written under five different pseudonyms entitled Poemas clandestinos, an act that seems to have alienated him further from the group’s leadership. There were whispers that he might be an American spy after all, that his 1964 escape was no escape at all but a reward for collaborating, though one wonders whether this absurd charge was simply an excuse. He was murdered by his own comrades along with another rebel, Armando Arteaga, in May 1975.

Dalton reminded us of the responsibilities that we have toward each other and that writers don’t live in a vacuum. “Poetry”, he wrote, “like bread, is for everyone”.

Looking for Trouble is published by Smokestack Books and availabel at http://smokestack-books.co.uk/book.php?book=118

£8.99