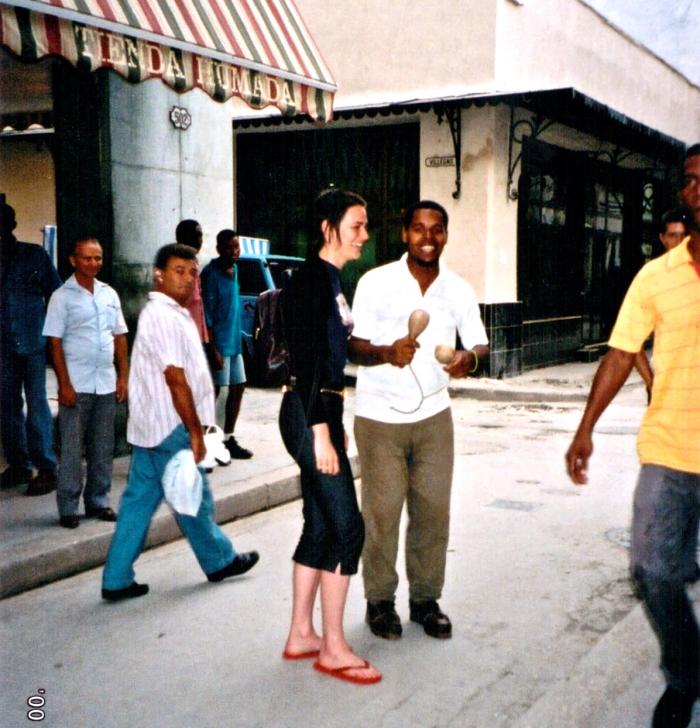

‘What I keep noticing here is the eyes and warmth. I am drawn like a seed into the warmth. Human arms reach out to enclose me from the harsh detachment of my mother tongue.’ This is me, writing in my notebook at the start of it all. It was 2000 – I had gone to Cuba for a holiday. I stayed, on and off over the next six years, to write.

Cuba inspires love. If you stay for any length of time, you will become very close to the Cubans in your life.

But make too many wrong assumptions and you could be plotting a rough course. Ordinary tests of a relationship are magnified and put under enormous stress by the economic and political inequalities inherent in your situation. Tourists and Cubans don’t necessarily want the same things when they get close – the desires for freedom, money and sex act as powerful incentives for each party to tailor their truth. Friendships can be hard to gauge, trust elusive, and authenticity measured according to different criteria by each party.

It was this inability really to know that made Cuba such a fascinating place for me as a writer – a place where every layer came away to reveal not ‘reality’ but another riddle. This is what inspired me to write Breathe, my short story collection about the struggle for intimacy and understanding between visitors to the island and the Cubans they encounter there.

Early on, I took dancing lessons from a teacher in Vedado – let’s call him Jose. He waited daily for his English girlfriend to arrive. I knew her – she’d given me a letter to deliver to him, come all the way out to Gatwick to put it in my hand. Jose’s Cuban girlfriend was very present – she lived with him, was there when we sat with friends late into the night. But as soon as the English girlfriend arrived, the Cuban one moved out. At my next lesson, the Cubana was there mopping the floor, reduced to the status of cleaner, incognito.

It is impossible to know someone, or judge the reality of what you have with them after just one or two short visits. If you go back and forth, each trip will serve as a romantic distraction from your everyday life. Mostly, the tourist will get the Cuban out of the country early in the relationship, never experiencing the reality of their Cuban partner’s world.

Some of the best relationships are those that remain on the island – dependency can break even a strong bond once the couple is living abroad. Staying in Cuba is a good way to test your relationship. You can learn Spanish, talk to your partner’s family and friends – see what’s really going on. You get more Cuban, which is a pleasure, and they find ways to accommodate you.

I lived with my novio in a flat in Havana. Later, we spent time with his family in the rural West – living in their home. It was a hard test for me, a way of life different from all I knew, but we learned to be close. I struggled with ways that charmed then confounded me. I adapted, and grew.

People warned me about relationships with Cubans who would try to exploit me, but I did not let them scare me; I trusted my judgment. Though we were from very different worlds, I an urban European, who made a living through writing, he a rural Cuban who made a living through fishing, I felt that I was capable of deciding whether he was a good man – and he was.

Life in Cuba is hard and tourists may try to buy their way into people’s affections – it’s a possibility, with our relative wealth, where someone is earning £13 a month. But anyone tempted to do so should think carefully about how they want the relationship to go – will it be one of mutuality, or will the foreigner have control and the Cuban hide their feelings due to economic need? Inequality twists the dynamics of relationships.

The power differential can poison even the best of connections. Long friendships that seem solid can crumble in seconds – it usually involves money. You have to decide on a deliberate policy together – this way it can work. So, for example, the non-Cuban can pay when you do tourist things, and the Cuban in the peso shops and bars. I knew people who bankrolled their Cuban friends, out of generosity or guilt – and the problem was, neither party could be sure why the other was really there. Often, both felt betrayed in the end.

How you fare with a cross-cultural relationship depends on what you mean when you say ‘love’ – and whether both parties share that meaning. In Europe ‘love’ is delicacy – a consumer item that we use to define ourselves. Cubans, in my experience, take a more realistic view.

A trauma psychologist once told me that people of all cultures use the world ‘love’ to describe a feeling they get when someone meets their needs. He said he had asked an Ethiopian woman who had been trafficked whom she could turn to for support – whom did she love? She said, ‘my husband, I love my husband.’ The psychologist asked her why, and she answered, ‘because he brings me food.’ It’s not romantic, but it makes a lot of sense.

Some people even dispense with the ‘love’ concept altogether. A close friend of mine, recently widowed, married a Cuban woman and brought her to England for a better life. There was no pretence of love between them, simply affection and respect. He did not expect her to love him; she made no promises to do so. But in the end, they have found a life in England together, quietly content.

* Leila Segal’s Breathe – Stories from Cuba (Flipped Eye Publishing) is out now. You can order a copy at http://www.amazon.co.uk