Unlike other South American countries, Brazil’s ‘Golden Age’ came really early, from 1908 to 1912. With typical panache, Brazilian filmmakers embarked on a rapid and fruitful series of short silent films that were hugely popular all over the country. Perhaps we should reflect on what it might have been like for those early audiences to experience moving pictures.

What previously had been tiny photographs with perforated edges in your hand (often seen in our grandparent’s collections) became transformed into huge moving images on a screen. The boundaries between reality and fiction did not yet exist in the mind of the spectators of this new art. One of the earliest films featuring a train coming towards camera, so terrified audiences, that they ran out of the theatre to avoid being mowed down. (The Great Train Robbery 1903). When my own grandfather screened a movie on a portable screen for the Mataco Indians in the Argentine Chaco, he found that when the characters left the room and closed the door behind them, the Indians ran around the back of the screen to see where they had gone. With experience, we have learnt how to ‘suspend disbelief’. Now we can watch a bear talking and accept it as perfectly normal, or experience a 3D image coming right at us, as in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Gravity’ (2013) without feeling the need to flee the theatre.

The Silent Era

Italo- Brazilian Affonso Segreto was the first person to start making silent films in Brazil in1898 and many others followed. These local productions were hugely popular. Most of these films are now lost but, at one point, passionate individuals with tiny budgets, were producing as many as 100 films a year, hence the title ‘belle époque’ for the period. There was no legislation relevant to the new industry and power supplies were so unreliable that it was rare to see films on schedule. This ‘Panorama do Rio de Janeiro’(1909) was only 4:06 minutes long, It was shot before Christ the Redeemer had been installed on the Corcovado mountain in Tijuca National Park. If you watch carefully, you might also see that Charlie Chaplin’s ‘funny walk’ was already alive and kicking in Rio de Janeiro!

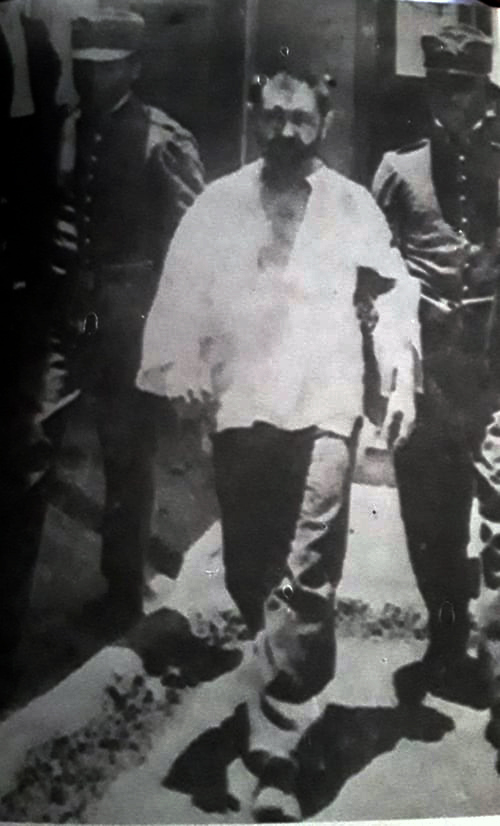

‘Os Estranguladores Do Rio’ (The Stranglers of Rio-1908) directed by the lead actor Francisco Marzullo (Carleto) and shot by Antônio Leal, was the first Brazilian silent feature to qualify as a local blockbuster, in a manner of speaking. It lasted around 40 minutes and was screened 830 times. A police drama, ‘The Stranglers’ was based on an event that took place in Rio de Janeiro in 1906, when a 19-year old lad was strangled and thrown into the sea after thieves ransacked his uncle’s jewellery store and he refused to give them the keys to the safe. It was the first Brazilian feature with a proper story, albeit taking some liberties with the truth and it caused a sensation, especially as it was sold as a true-crime drama.

'Os Estranguladores Do Rio (1908) Antônio Leal and Francisco Marzullo (also lead actor).

'Os Estranguladores Do Rio (1908) Antônio Leal and Francisco Marzullo (also lead actor).

Another very popular trick, as sound movies had not yet been developed, were “sung” films. The actors would hide behind the screen and dub themselves live, during the projections.

Glauber Rocha (later to be the star director of the Cinema Nôvo) considered Humberto Mauro’s drama ‘Ganga Bruta’ (Brutal Gang-1933) to be one of the finest Brazilian films ever made, even though it was not until 2015 that it was finally recognized by the Brazilian Film Critics Association. It tells the story of a man who kills his wife on their wedding night and then moves to a city where he becomes part of a love triangle.

Déa Selva and Durval Bellini in 'Ganga Bruta' (1933) by Humberto Maura

Déa Selva and Durval Bellini in 'Ganga Bruta' (1933) by Humberto Maura

One film that stands out from these early days, ‘Limite’ (The Boundary-1931), was the only film the 19- year old Mário Peixoto ever made. This silent, experimental feature film plays with time and inter- related narratives between three different characters, two women (Olga Breno and Tatiana Rey) and one man (Raul Schnoor). Using flashbacks and double exposures Peixoto reveals the reasons why these three people are aimlessly drifting in a boat, as they reach the limits of their very existence. Admired by Orson Welles, Eisenstein and Walter Salles, the film revels in existential angst. Antonioni and Godard were not to excel in that field till the 1960s. When Sergei Eisenstein saw the film in London in 1932, he described it as a fine example of the ‘pure language’ of cinema. It was too ahead of its time to do well at the box office, but today, having topped the list of the 30 most significant films in the history of Brazilian cinema, it is considered a masterpiece: -

The ‘Chanchadas’

In ‘Carnaval no Fogo’ (1949) director Watson Macedo’s style of musical comedy was credited with having inventing the ‘chanchada’ genre. In this clip we see a parody of the balcony scene in Romeo (played by Oscarito) and Juliet, (Grande Otelo) (No English Subtitles)

The 1930s also saw the founding of the Cinédia Studios by Adhemar Gonzaga. During its heyday, from the 1930s ‘till the mid-fifties, it produced a plethora of ‘chanchada’ films. These productions were derived from a combination of the Hollywood stage ‘revues’and musicals, Brazilian comic theatre, dance and the spirit of carnival. Stars were made as, needless to say, the films ‘Alô,Alô Brasil (1935)’ and ‘Alô, Alô Carnaval (1936)’ (Hello, Hello Brazil and Hello, Hello Carnival) catapulted the Portuguese-born Carmen Miranda into the spotlight as a dancer, actress and singer, especially once she had caught the eye of Hollywood. She became very famous, noted for her penchant of wearing fruit for a hat. At least she never went hungry!

Carmen Miranda and Andy Russell

Carmen Miranda and Andy Russell

At about that time, the Atlântida Studios started to react to this genre, by committing themselves to producing socially-committed films with European-style realism. But, to pay the bills, they had to resort to the ever popular ‘chanchadas’ and they then went on to perfect the form. They teamed up with the two most loved Brazilian comedians of all time, Oscarito (1906-1970) who started out as a circus clown and the tiny black Grande Otelo (1915-1993) who would end up being the butt of his jokes, (there was little questioning of the level of racism at the time). This pair often worked with the just as tiny (1.50m high) of comediennes, Dercy Gonçalves (Dolores Gonçalves Costa) who went on to have the ‘Longest Career as an Actress’ according to the Guinness Book of Records (86 years). She died in 2008 of pneumonia at the age of 101.

Chanchada films worked around a classic formula: A girl and lad are in danger. A comic who tries to help them is hopeless, so the villain terrorizes them. There is a final denouement which then leads to a happy ending. There are elements that are reminiscent of Benny Hill comedies or Carry-on Films, with more dance and pageant. Though erotic, initially at least, they avoided explicit sex, and significantly, as they did not criticize the government, they had few problems with production. The rigid political censorship did not extend to the chanchadas and the state-sponsored Embrafilme Studio was happy to support them.

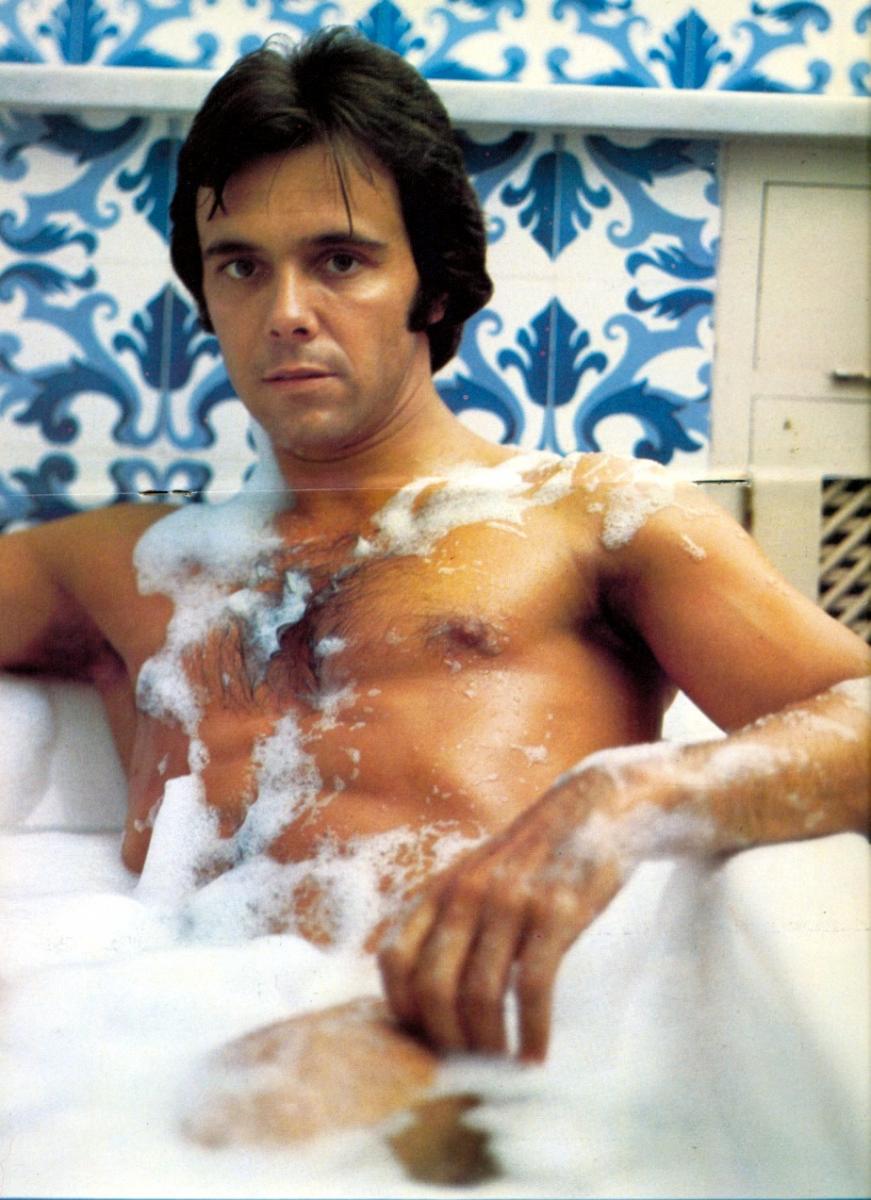

Most chanchadas were produced in the downtown quarter of São Paulo known as the ‘Boca do Lixo’ (Garbage mouth) and some studios developed them into a subgenre known as ‘pornochanchada’ which became so hardcore (with the help of clandestine video cassettes) that it explored itself to death. People began to complain that Pornochanchadas “transgressed conservative sexual behaviour and portrayed the privileged fiction of the Macho figure, negatively impacting the role of the woman in society” (Amen!) Prominent actresses were Helena Ramos and Aldine Müller, and, among the men, the ‘sex-bomb’ David Cardoso (considered the epitome of Brazilian Machismo and king of the pornochanchadas) and Nuno Leal Maia.

David Cardoso, actor and director.

David Cardoso, actor and director.

David Cardoso with a selection of his nymphs

David Cardoso with a selection of his nymphs

Though many went too far, the bulk of the chanchada films were less explicit and expressed the Brazilian love of music, movement and the human form which is almost a cult in Brazil. Today young men work out on the beaches and girls parade their bodies naturally without feeling the need to ‘compete’. When it comes to Brazil, things must be seen in context and the typical Brazilian is not an exhibitionist; it runs far deeper, sensuality and physicality being part of how life itself is perceived. It could be argued that the chanchadas only existed thanks to the subliminal influences of the country’s rich Amerindian and Afro-Brazilian heritage.

0 Cangaceiro (1953) Lima Barreto

0 Cangaceiro (1953) Lima Barreto

Much like the Atlântida Studio before them, the Vera Cruz Studio of São Paulo was set up to work against the perceived vulgarity of chanchadas. They had one big success ‘O Cangaceiro’ (The Bandit- 1953) directed by Lima Barreto. Barreto had been invited to join Vera Cruz by its president Alberto Cavalcanti and they reluctantly agreed to produce his Brazilian adventure-western. It ended up breaking box office records and winning two awards at Cannes. The story was based on the most famous bandit leader in Brazil, Lampião, of the Cangaço, (a form of banditry prevalent in the Northeast of Brazil). Cangaço had originated in the late 19th century but Lampião, born in the state of Pernambuco, accompanied by his lady Maria Bonita, led a band of upto 100 cangaceiros who fought successful actions against the paramilitary police in the 1920s. These exploits turned him into Brazil’s equivalent of Jesse James, Billy the Kid or Pancho Villa. The film also included the hit number O’Cangaceiro: Mulher Rendeira (The Lace Maker)- a song that was to become the battle hymn of the cangaceiros (and later, to be popularised by Joan Baez).

Cinema Nôvo

However, these sophisticated European-orientated productions were not box-office successes in Brazil and after producing only 18 films the Vera Cruz Studio went bankrupt. Alberto Cavalcanti, who had left before the bankrupcy (maybe he was fired) made two more films for another company, including ‘O Canto do Mar’ (Song of the Sea 1953), which in their realism, are considered to have opened the door to the greatest period of Brazilian cinema, the Cinema Nôvo of the 1960s. Another key player was Nelson Pereira dos Santos who became the ‘guru’ or ‘father’ of the movement. With his film ‘Rio Quarenta Grous (Rio, 40° 1954) he introduced the idea of independent low-budget filmmaking that characterized the Cinema Nôvo. ‘Rio 40°’ has a documentary feel as it follows five boys from a hillside favela (shanty town) who sell peanuts at the beaches, popular tourist spots and football games.

With this production, the magic of Italian Neo-realism had finally reached South America. Under the influence of Dos Santos, who disliked the artificiality of Hollywood, Brazilian directors began to shoot on location, using non- professional actors and dealing with contemporary issues that were popular in a simple, non- dramatic way. Urban and rural deprivations were chosen as subject matter, coupled with themes such as starvation, religious alienation and economic exploitation. At that time, given the left-wing government of João 'Jango' Goulart, young film makers were full of optimism and hope.

When director Glauber Rocha (1939- 1981) filmed the impressive and visually stunning ‘Barravento’ (The Turning Wind 1962), it was still before the Military coup d'état of 1964. It is the story of a Bahiano from a fishing community, which is divided between religious alienation and progress, as well as past and present fishing methods. With Eisensteinian montage sequences and delirious camera moves, predicting the famous sequel, ‘Antonio Das Mortes’. Because Brazilian films found themselves unable to complete with ‘foreign’ imports and a public that had become accustomed to North-American entertainment ideology, Rocha emphasized the need for cinema to be for the poor, filmed on low- budgets and be cheap to view. Rocha did not leave room for doubt on his views.

Glauber Rocha proved to be one of the most influential film makers in Brazil and his work epitomized the Cinema Nôvo. Among his best films is ‘Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol’ (Black God, White Devil 1964), literally translated as ‘God and the Devil in the Land of the Sun’. This film, set during a drought in the ‘sertão’ (the hard hinterlands of NE Brazil) pits a man against his boss who is trying to cheat him and he becomes an outlaw fleeing with his wife, who is also drawn into violence when they join a self- proclaimed saint’s entourage. It is realistic, but Rocha blends religion, popular customs, culture and mysticism in this entanglement of cultures and religions where a man has to find his own path.

Black God, White Devil (1964) Dir: Glauber Rocha

Black God, White Devil (1964) Dir: Glauber Rocha

In this powerful sequel to ‘Barravento’, ‘Antonio Das Mortes’ (1969), the hired gunman Antonio das Mortes (Mauricio do Valle) has to return to action when, despite killing the last cangaceiro almost 30 years earlier, a new outlaw appears who turns out to be an idealist. Antonio is deeply affected when he witnesses the fall of a common rural worker as he enters a life of crime,by joining the gang of his hated enemy Corisco, the Blond Devil (Othon Bastos). Eventually this leads to the Pedra Bonita massacre. This film has the melodrama and flamboyance of a spaghetti western. It won the Prix de la Mise-en-Scène at Cannes 1969.

Barravento- samba and capoeira scene

In 1967, the Military government enacted a new restrictive constitution, brutally censoring free speech and any political opposition. This became known as the second coup and it became almost impossible for Cinema Nôvo films to be screened. A group of directors founded the studio Difilm with a commercial producer, Luis Carlos Barreto, to make more commercially viable films like ‘Macunaïma’ (1969) by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade.

Grande Otelo being born in Macunaïma ( 1969) by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

Grande Otelo being born in Macunaïma ( 1969) by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

Based on Mário de Andrade’s (no relation) novel of the same name, ‘Macunaïma’ is a key film of the movement known as ‘cannibal- tropicalist’. This represents the last phase of the Cinema Nôvo. Recalling some of the qualities of the original ‘chanchadas’, the film humorously satirizes the hypocrisy of Brazil’s illusion of an harmonious racial mix. It also plays as an allegory of the turmoil of the Military regime. The great comedian Grande Otelo, already in his 60s, plays the title character macunaïma as a baby, who is miraculously born to an old woman (Paulo José). With carnivalesque, and cannibalesque mises-en-scène, the characters try to avoid being eaten- they articulate absurd dialogues and inappropriate songs. It is hugely entertaining and the result is a harsh critique of contemporary Brazilian Society. The title character, Macunaïma ends up in the Amazonian jungle surrounded by the colours of the Brazilian flag. When he jumps into a river to follow the elusive goddess Uiara, all that remains is blood and his green jacket, as Andrade explained: “Macunaïma is the story of a Brazilian devoured by Brazil”.

A series of udigrudi, (a corruption of the word 'underground') films, exploded on the film scene in 1967 and petered out in the mid- 1970s after about 30 films. Produced during the harshest and most brutal period of the Military regime, they are deliberately nihilistic and violated established ideas of 'crowd-pleasing' movies with comprehensible storylines. Also called the Cinema Marginal movement and Cinema de Invenção, (of invention) these filmmakers rejected what they called the ‘Cinema Nôvo Richo’ (Nouveau- riche cinema). They had films with interesting titles like Júlio Bressane’s ‘Matou a Família e Foi au Cinema (Killed his family and Went to the Cinema, 1969) or Rogério Sganzerla’s ‘Red Light Bandit’ (1968). On the whole, however, the 1970s was a commercially productive period. The INC (National Film Institute) was founded, state subsidies were introduced, and Embrafilme was created to promote Brazilian films worldwide.

True to the fun soul of the Brazilians, erotic comedies continued to thrive. One hilariously witty gem is the filmic adaptation of Jorge Amado’s ‘Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos’ (Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands-1976). Directed by Bruno Barreto, it is set in Bahia during the 1940s, it is remembered for introducing the stunning Sônia Braga. The film broke box office records, was nominated for a Golden Globe and won the Best Leading Newcomer award for Sônia Braga at the Baftas. When her wild, sexy but irresponsible husband (José Wilker) dies, his widow, Dona Flor (Sônia Braga) remarries. Just as she discovers that her new love life with the local Pharmacist Dr Teodoro Madureira (Maura Mendonça) is sadly lacking in sparkle, the ghost of her late husband unexpectedly returns. Not to be missed! Twenty years later he was to film '4 Days in September' about the abduction of the American Ambassador Charles Burke Elbrick by the MR-8 guerrilla group.The film was written by Fernando Gabeiro, one of the kidnappers, adapted from his own novel about the event, 'O Que é Isso, Companheiro'.

‘Dona Flor and her Two Husbands’ also features the wonderful music of Chico Buarque and the theme tune of “O que sera, que sera”. Buarque fans can listen to the full album of the film music: https://youtu.be/rdQ1d53RjXs

Anna Muylaert

Anna Muylaert

Gradually more women have been participating prominently in the film industry with ‘Mar de Rosas’ (Sea of Roses 1977) by Ana Carolina, Gaijin (1980) by Japanese- Brazilian Tizuka Yamasaki, and Susana Amaral’s ‘A hora da Estrela (The House of the Star- 1985. More recently, Anna Muylaert had success with her moving films Smoke Gets in Your Eyes (2009) and Durval Records (2002), and The Second Mother (2015).

Argentine-born Héctor Babenco was also deeply influenced by Italian neo-realism.

Héctor Babenco ( 1946-2016).

Héctor Babenco ( 1946-2016).

Having fled an unhappy home at an early age, Babenco settled in Europe before ending up in Brazil. There he embarked on his film career producing an amazing clutch of films starting with 'Peixote: A Lei do Mais Fraco (Pixote:(small child) the Law of the Weakest-1980). Based on the book ‘The Childhood of the Dead Ones’ by José Louzeiro, it recalls Luis Buñuel’s ‘Los Olvidados’ 1950). This chilling documentary- style drama deals with the short and excruciatingly hard lives of young delinquents who are manipulated both by corrupt police and other criminals into a life of crime. The lead, Peixote, was played by Fernando Ramos da Silva who returned to his delinquent ways after filming and was eventually shot dead by the São Paulo police at the tender age of 19.

In the early 1990s, political upheavals led to financial downturns in the economy. Embrafilme and other studios collapsed, so that in 1991, only 9 films were released. After 1995, some state subsidies and fiscal exemptions were introduced. But, by the time the decade was knocking on the door of the new millennium, things had started to improve exponentially. Among the productions that made an impact is Héctor Babenco’s true-life drama ‘Carandiru’(2003), based on the writing of Dr Varella. Babenco, who was also Dr Varella's patient, persuaded him to write about his time working for an HIV campaign in the overcrowded penitentiary in Rio called Carandirú. In the jail, some of the most violent and vulnerable elements of Rio society were pushed together with disastrous results. Babenco adapted the Doctor’s memoirs and with his deep humanity and capacity to understand the foibles of human nature and the violence behind them, he created this moving film, one of the best of its kind. This film is sad, terrifying, poignant and violent, another gem!

Bruno Barreto’s ‘O que e Isso, Companheiro’ (Four Days in September 1997) was nominated for the U.S. Academy Award for Best Foreign Language film. It is a fictional version of the 1969 kidnapping in Rio de Janeiro of the US Ambassador to Brazil, Charles Burke Elbrick (Alan Arkin) by members of the Revolutionary Movement 8th October (MR-8) and the ALN (Ação Libertadora Nacional). It explores the ‘journey’ of one of the kidnappers, Paulo, played by Pedro Cardoso. Fernando Gabeira, who wrote the screenplay, also participated in the kidnapping and is represented by Paulo. It explores his love affair with the guerrilla leader Andréia, and the friendship that develops between the kidnapper and his victim.

Another successful film to hit the international screens was Walter Salles’ endearing ‘Central do Brasil’ (Central Station (1998). Starring Fernanda Montenegro and Vinícius de Oliveira. It tells the story of young Josué’s friendship with Dora, a jaded middle- aged woman who makes a living writing letters for illiterate customers at Rio de Janeiro’s Central Railway Station, letters she does not always bother to post. Walter Salles’ unsentimental and gentle observations, plus his attention to detail leads Fernanda Montenegro on an emotional journey as the cynical Dora, with a superbly nuanced performance. Montenegro was rightly awarded the first and only Best Actress Oscar to be won by a Brazilian actor, as well as numerous awards at other festivals, including the Silver Bear in Berlin. The film itself won the Golden Bear in Berlin and was nominated for the Oscars. The list is endless. Not least because it surpassed ‘Dona Floor and her Two husbands’, as the highest–grossing Brazilian film in the USA.

Central Station (1998) Dir: Walter Salles

This record remained unbeaten until the release of ‘Cidade de Deus’ (City of God- 2002). This immensely moving, hard-hitting thriller is set in the ‘favelas’ of Rio de Janeiro. The paths of two kids collide, as one struggles to fulfil his dream of becoming a photographer and the other becomes a kingpin in his little fiefdom. Directed by Fernando Meirelles and co-director Kátia Lund, it stars Alexandre Rodrigues and Leandro Firmino. It was nominated for 4 Oscars, while gathering another 75 wins and 44 further nominations.

City of God (2002) Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund

In an effort to decentralize film production, a strong film base has been developing in Fortaleza and Ceará in the north east of the country. Many directors like Karim Aïnouz, Madame Satã (2002) and The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmão (2019), Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles, Guto Parente, Cannibal Club (2018) and Inferninho (2018), have been producing award-winning films.

Kleber Mendonça Filho has made his name with films of great subtlety, that nevertheless are rooted in irony and sharp comments about the social conditions in Brazil. His first feature-length drama ‘O Soma o Redor’ (Neighbouring Sounds 2013) won numerous awards and was picked out as a favourite by musician Caetano Veloso. Gentle and captivating, without needing to resort to melodrama, his films uses humour and warmth. This is also visible in ‘Aquarius’, his subsequent feature (2016) that starred the magnificent Sônia Braga and developed his ideas further.

Neighbouring Sounds (2013) Kleber Mendonça Filho

Neighbouring Sounds (2013) Kleber Mendonça Filho

Now, three years later, his latest film, ‘Bacurau’(2018) has a very different take. Written and co-directed with Juliano Dornelles, it won the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival. ‘Bacurau’ is a dark, drug-fuelled, mysterious, and at times, almost psychedelic, western set in the sertão (badlands) of north-eastern Brazil. It builds up tension as strange happenings in a small town gradually begin to reveal what is behind the terror and how the local villagers are having to fight for survival. With Udo Kier, Barbara Colen and Sonia Braga and the remarkable Silvero Pereira as Lunga, the film has layer upon layer of interest, both literally and emotionally.

Brazilian cinema has proved to be the most varied, surprising and inventive in South America. It developed a distinct identity and personal way of expressing its stories. There is music at its heart, together with a social conscience that is never far from the surface, to be seen even in the simplest comedies. Despite powerful influences from Europe and Hollywood, Brazil always managed to re-create these in its own image with its own complex and rich cultures intertwined. There is a huge amount of originality and new productions are still flowing, even now. Given the economic situation with its many financial difficulties, it is clear that Brazilian directors are having to find new and unexpected ways to survive yet again.

For more information please see: -

Aquarius Kleber Mendonça Filho: https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/search-new-brazil Bacurau: https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/‘bacurau’-2019-dir-juliano-dornelles-kleber-mendonça-filho Héctor Babenco: Memorable films: https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/memorable-films-hectór-babenco-an… Guto Parente: Inferninho (2018) https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/my-own-private-hell-inferninho-20… Anna Muylaert: The Second Mother https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/brazils-social-realism