There’s no need to have any contact with Brazil to come across its most iconic musical genre. So famous is ‘The Samba’ that this music and dance has even spawned poor relations across the world, mostly via Saturday night TV in the form of ‘Strictly’ and or whatever local version.

Among the uncountable genres, rhythms and forms of Brazilian music, none is as well-known or has the same national and international penetration as Samba. In 2016 Brazil celebrated the centenary of this genre, even though her presence in Brazilian music dates from far before. 1916 was the year when the first recording of a music defined as Samba appeared in Brazil, with the song ‘Pelo Telefone’ composed by Donga. This seminal track inaugurated a singular place for Samba in Brazil’s music scene.

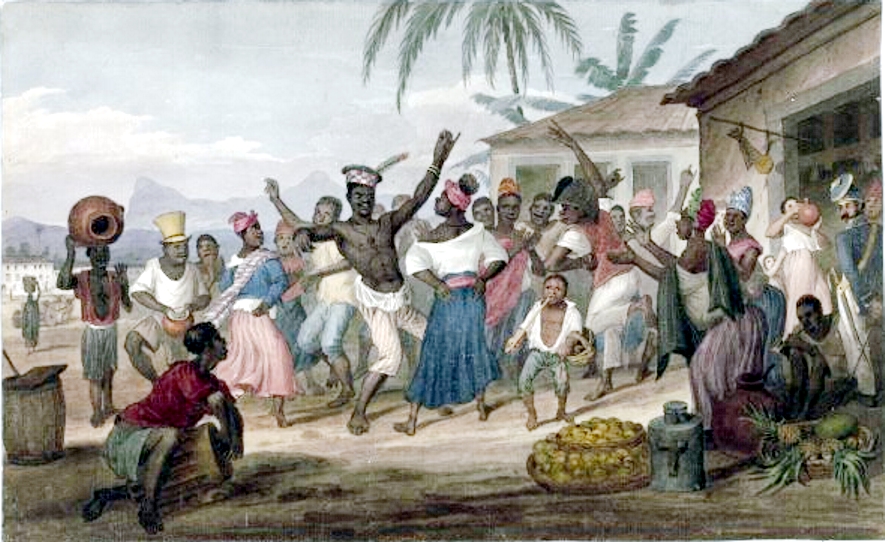

It is very difficult to trace the origins of Samba. One thing is for sure, it was a musical form developed among the Africans and Afro-descendants in Brazil who were enslaved and suffered the most inhuman conditions one can imagine. Black slavery was only abolished in Brazil in 1888. By that time, their music was already acquiring a peculiar configuration, incorporating European forms and generating the core elements of what would be later called Samba.

The exact location of its origin is also disputed. Many cite the state of Bahia, in Northeast of Brazil, others Rio de Janeiro. The word, however, has been used in many other parts of Brazil, such as Minas Gerais and São Paulo, at the same period, always referring to musical practices among slaves or former slaves. It was a music marked by irregular melodic and rhythmic syncopation, normally associated with a dance and accompanied by percussion. The strong presence of percussion instruments is behind another term commonly associated with Samba, the ‘batucada’. Batucar, in Portuguese, means literally to play the drums. By extension, batucada is a drums ensemble or a music performed with several percussion instruments.

Yet even without a clear definition of its origins, Samba became a sort of musical national identity in Brazil. It developed and spawned many names to express its plurality and richness; samba-canção, samba de beque, samba de partido alto, samba-choro, samba reggae, samba de pagode, samba de enredo, samba exaltação, samba rural, samba de bossa nova, samba de raiz, and many others. Each variety qualifying nuances, developments or peculiarities as the genre incorporated diverse cultural sources and influences.

Those names not only specify the diversity of Samba, they are testimony to the immense flexibility of a musical genre, constantly changing as it incorporates influences, defining Samba exactly by its non-definition.

It is rare to find a Brazilian singer or songwriter that has not recorded or composed a Samba. Despite its association with Rio de Janeiro’s carnival, thanks to the ‘schools of samba’, the genre cannot be reduced to an area in Brazil.

What she has, clearly, in her very definition, is a social as well as aesthetic nature: in all her expressions, Samba has been a voice of the oppressed, a voice of those neglected by an unequal and racist society. She includes, she protests, and she echoes the chants of Brazil’s African slaves, who found, in this music, a way of keeping their strength and hope.

Samba is the voice that one doesn’t simply hear, but needs to incorporate and embody; she demands movement, performance, dance. But everyone knows that, despite being associated with happiness, dance and celebration, Samba always conserves a painful claim. Vinicius de Morais, another worldwide known Brazilian poet and composer, author of ‘The Girl from Ipanema’, wrote in his ‘samba da benção’

Because the Samba was born in Bahia

and if it is today white in its poetry

it is black at heart

…And to compose a real samba

requires a lot of sadness

or you will never compose a samba….

Samba is sadness swinging

and sadness always hopes

of not being sad anymore

Essentially Samba is the struggle for expression, it has given a voice to powerless people in an unequal country and an unequal world. Through it they find reasons to singing, dance, and celebrate.

And in this way, with its social and existential connection, Samba assured its sacred place in Brazilian music and in the very identity of Brazil. To experience Samba is not only an aesthetic matter, it's a real exercise of otherness and Brazilianity, it is to embrace and be embraced by Brazil, with all its social dilemmas. To not like Samba is to be unBrazilian. As another old Samba song affirms:

Quem não gosta de samba/ If you don’t like Samba

bom sujeito não é/ You’re not a good citizen

é ruim da cabeça/ Or you’re crazy

ou doente do pé/ Or there’s something wrong with your feet.

Vinicius Mariano de Carvalho is Senior Lecturer at King’s College London