Lisbon, until 2004 the undiscovered jewel in western Europe, is home to the haunting Fado music made popular by Mariza and Cristina Branco. Besides urban Fado music, which is internationally known, Portugal has a huge variety of regional music on the mainland and on the islands of Madeira and The Azores.

Regional music has suffered from progressive urbanization and the growth of mass culture, but it is kept alive by local groups and features in summer festivals. In the northern region of Tras-os-Montes groups play bagpipes and dance with sticks as in the English Morris Dance, and unaccompanied singers still sing in the ancient Mirandés language. In the southern region of Alentejo there is a tradition of polyphonic male-voice choirs. Folk music revived as the Salazar dictatorship ended in 1974, and musicians like José Afonso began to explore new combinations of styles.

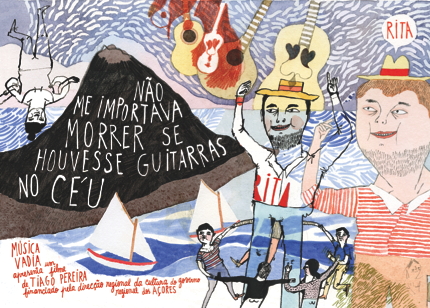

I spoke to Tiago Pereira whose latest documentary film is focused on the dance music called the Chamarita, unique to the islands of Pico and Faial in the Azores. He is also a mixing artist who uses electronica with traditional rhythms to make videos and soundscapes, and he talks with such tense energy that I expect him to be chain-smoking. About the music and its cultural and historical significance, and its neglect by mainstream urban culture.

Latinolife: One of the images which struck me was the Viola de Terra, with the 2 hearts, one pointing away and one pointing back. Can you talk a bit more about that?

Tiago Pereira: It’s very typical of the Azores. They have a profound sense of ‘saudade’ but it’s different from the ‘saudade’ on the mainland. There are always people coming and people leaving, and this figures in the popular symbolism, the two hearts are joined in the form of a teardrop, the teardrop of sadness. It’s a kind of eternal saudade.

LL: This word ‘saudade’ is used a lot in Portuguese and it doesn’t have an equivalent in English.

TP: Especially in the Azores, because they are in the middle of the Atlantic, halfway between Europe and America. so it is saudade for the places they went to as well as those they came from, in Europe. The United States is super-important for the Azoreans. They use English words like ‘vacuum cleaner’ instead of ‘aspiradora’, or ‘freezer’ instead of ‘frigorifico’. The iconography of the viola too, it has a mirror above the neck, which is something from the US culture of glamour which is not Portuguese.

LL: I noticed in the film that people talked passionately about the music as something that bursts forth within the community, and also from the earth, like a volcano.

TP: Yes, the islands are volcanic, and the people see the Chamaritas in this way. Many dances in the islands to the west are slow, melodic. It’s only in those 2 islands in the centre, Pico and Faial, where the music is more rock&roll, and they are the islands where volcanic activity is stronger. They sense that people are very close to the earth and the earth is very Chamarita - they say that Pico was Chamarita and Chamarita was Pico. On Pico and Faial you see all those vineyards and think these people are crazy,how did they make such a thing ? it’s a struggle against nature. The Chamarita is like a victory dance, humans have defeated nature, the volcano, and succeeded in making the land productive. The Chamarita is also a productive dance, where people are made to be infected by the music, people can’t but dance, and move, and shake.

LL: The best known music from Portugal is Fado. I believe it used to be a dance, not music to sit and listen to. So the Chamarita has not lost this aspect?

TP: It was once for dancing and today it’s seen as the typical music of Portugal, but its popularity has trampled over the knowledge of all the others. The Fado ‘Batido’ is a very fast dance that was very popular in the 30’s-40’s but has been forgotten now. The Fado that everybody knows nowadays is from Lisbon, it’s an urban music.

LL: From what you say, the culture of the Azores is oriented on an East-west axis, Africa doesn’t come into the picture ?

TP: Africa no, but Latin America does, many people say that the Chamarita is a Brazilian dance, and there is a Chamarita that is very strong in Bolivia and Venezuela. In Florianopolis in Brazil they say it isn’t Azoreano. So we don’t know where it comes from, it could have come from Portugal, but it was transmitted by the explorers, and it has very strong Anglo-Saxon and Latin American influences as well as Portuguese. But any music that has power, guts comes from a Rock and Roll influence. On the mainland, we don’t have any dances that are so fast. You can really feel it, the speed it’s frenetic, it comes from an Anglo-Saxon culture.

LL: How important are the words in the Chamarita?

TP: Very important, because in its origins it was like a kind of Rap, nowadays it’s more a written form: I say something, you say something else to counterpoint mine. But even though it’s written, the artists improvise. It uses popular sayings, like in the film when people say “viola, my viola, viola my wife, a woman you can touch whenever you want”, or: ”every girl is like a ripe fruit when she’s born everyone wants to eat her”. They have a very hard life in the fields, and while they are working they are thinking about the words, the ballads.

LL: In the film you see people of all ages dancing, it seems to be a tradition that is still very alive.

TP: These days people get together every weekend to dance Chamaritas. All the generations, it is an organic part of life, it’s part of them, its incredible. Like Fado in Lisbon.

LL: How does this film fit into the larger project?

TP: I’ve got a project on Canal de Videos on the internet, called Musica Portuguesa Gostada Propria, which tries to showcase Portuguese music that is unknown to the Portuguese music industry. I record music that is not known, musicians from all parts of the country who’ve never recorded discs. There is a very strong prejudice against popular music in Portugal, because of the 25 April revolution. The fascist influence under Salazar was very strong, they idealized country music and peasant life. During the Estado Novo they made a lot of the ‘splendor folklorico’, and turned it into a symbol for political ends. So after the revolution the public rejected this kind of music. It was seen as representing fascist art, and as idealizing rural life which had a kind of spiritual poverty. So urban people don’t know this music, which means that Portuguese music is not well-known. So we record music in the streets, and other places with the idea of revealing a music that hardly anyone knows.

When I said I was going to make a film about Chamarita in the Azores, people thought it was about a place called Chamarita, which shows that people are absolutely ignorant about their own music.

Nowadays, with Fado being recognized as a Cultural World Heritage, it has become known outside Portugal, but this contributes to the trampling underfoot of the great musical richness which such a small country has produced. It has an infinite variety, of instruments, of ways of singing, from the north to the south and the islands. Traditional music in Madeira has been influenced by Mauretanian music, and other African styles. Music from the Algarve is slower; that from the Alentejo is related to children’s games. Then there is the very loud shrieking style of singing ‘ ao guincho’.

And the instruments: the Portuguese guitar is different from the usual Spanish kind, and concertinas and Sarroncas. Portuguese people are very inventive, they can turn anything into a musical instrument.

LL: Your next project?

TP: To make a film about the Viola Camponesa, from the Alentejo, which is unique in accompanying singing, as if it were another voice, and it is practically identical with the Viola Caipira from Brazil. It is being recognized very slowly here, as we are about 30 years behind Brazil.

LL: What did you do before you started to make these documentaries ?

TP: I also do mixing, making videos in real-time, video-samplers. My father played traditional music but later I discovered electronic music, and before making videos I recorded the sounds of the countryside. A soundscape was the most difficult thing to understand. DJ Spooky, and all these things to do with Remixing, which is part of 21st century culture.

But you can’t make remixes if you don’t have the archived material. The more archived material, the better the opportunities for making Remix. I grew up with traditional music, so I’m interested in an art form that is close to my roots, that records the roots of things, but at the same time to mix them with electronica.

As you saw in the film, we made an electronic Chamarita, made from the same chords, in B Major.