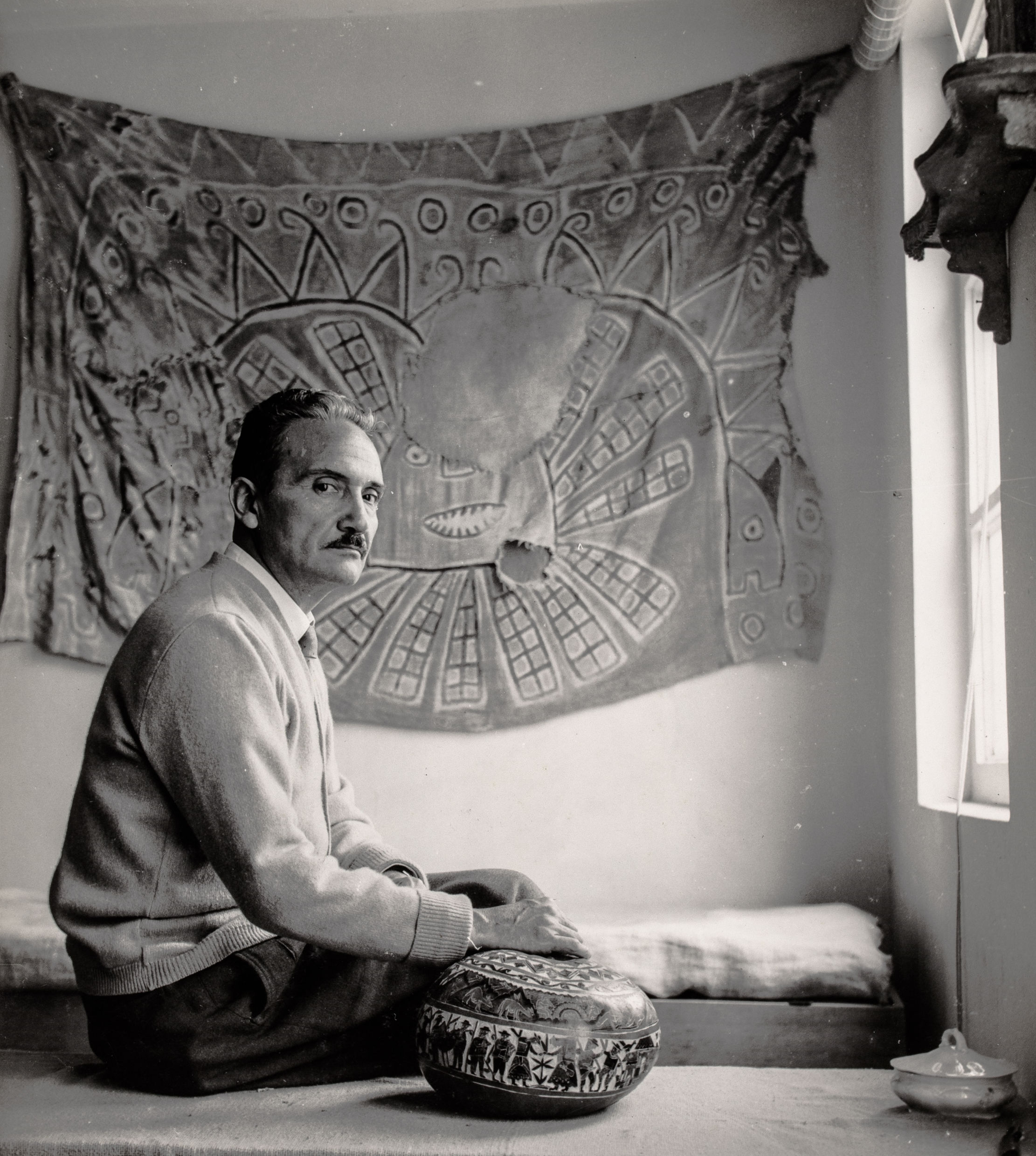

José María Arguedas was one of a kind. Though of Spanish descent, he referred to Quechua, the most widely spoken Indigenous language in the Americas with 8 million speakers today, as his maternal tongue. Raised by the indigenous servants of his stepmother, owing to the death of his mother when he was two and the absence of his itinerant father, Arguedas grew up speaking and loving the Quechua language. As a writer, he went on to champion the indigenista movement, giving great importance to a language and culture derided as inferior and backward by the Spanish-speaking literary and political elite across Latin America.

Arguedas said the Quechua language contained “the very matter of man and nature and the intense link that still exists between them.” From his bilingual perspective, he acted as a bridge between the Quechua and Hispanic worlds – incorporating his childhood universe and affinity with nature into Peru’s colonising and industrialising ‘modernity.’ He advocated a modern Peru capable of genuinely respecting its Indigenous origins.

At a time when Latin American politics and nation building projects were still enforcing a civilisation vs. barbarism (or nature vs. culture) paradigm that marginalised Indigenous thought, Arguedas was a proponent of the Quechua worldview, known for an animist understanding of humans and nature; entangled and relational, rather than existing as oppositional entities.

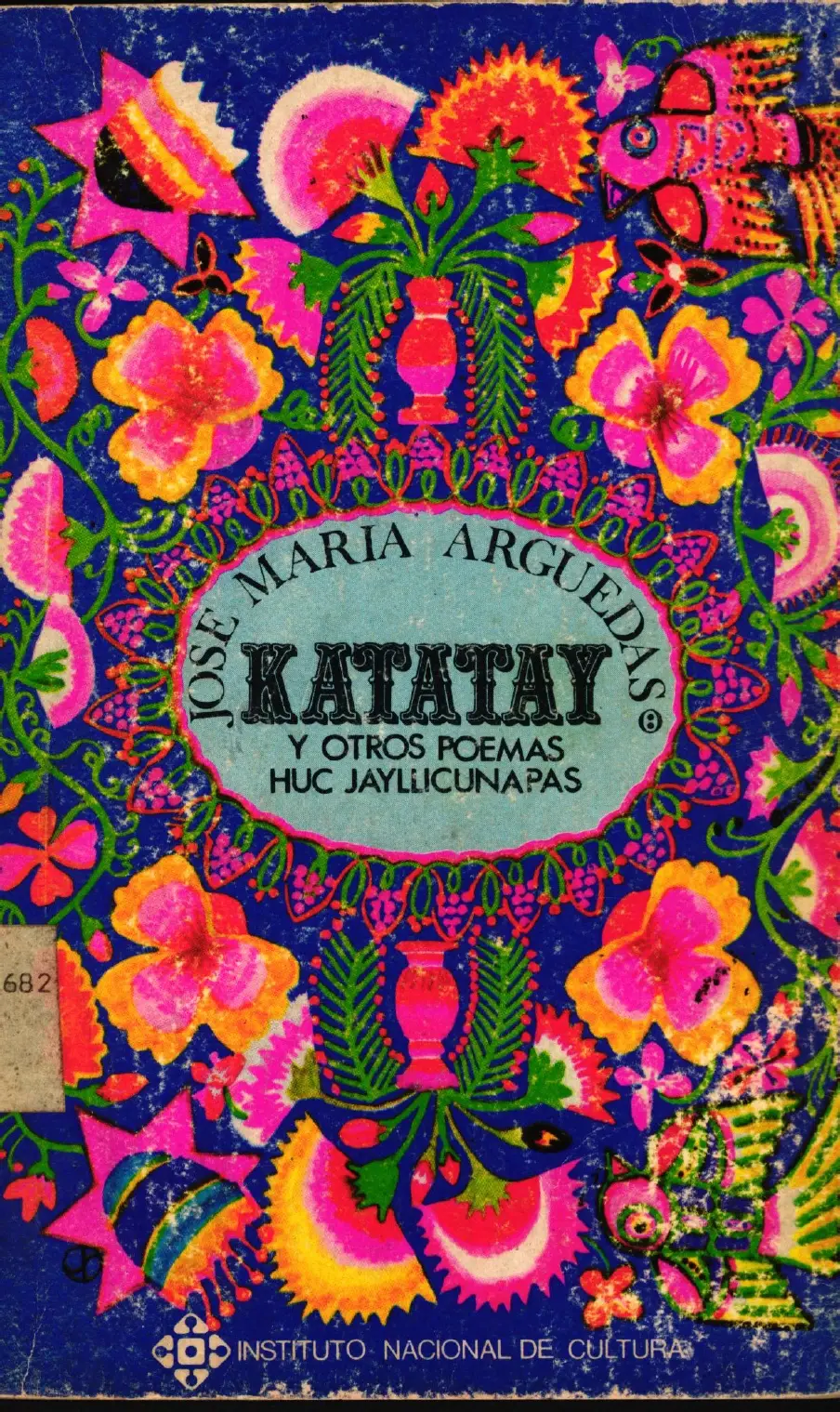

His 1972 poetry collection in Quechua Katatay (literally ‘shake’ in reference to an earthquake), explored the Quechua values of reciprocity with nature in the modern world. He describes the moving conservation he has with a tree in a square in Arequipa, Peru:

“I spoke to it with respect. It was for me something very intimate and at the same time from another hierarchy… I heard its voice.”

Challenging the hierarchy of Eurocentric knowledge, Arguedas describes the voice of the tree as “music that neither Bach, Vivaldi or Wagner could make so intensely and transparently full of knowledge, love and as penetrating as a dream, from the very same material that we are all made out of.”

Through his novels, essays and poems, he advocated the Quechua idea of ‘decolonising nature,’ as opposed to treating nature as a subservient object, property, or a source of scientific information for human use. He offered a paradigm that tore down the divisions between nature and culture characterised by the Peruvian president at the time, Fernando Belaúnde, who defined the Amazon as “the cheapest land in all Peru.”

While his influence on Peruvian literature was great, Arguedes was looked down on by the international Latin American literary canon, as a ‘provincial’ writer. He was famously caught up in a polemic with experimental Argentine writer Julio Cortázar. He believed that writing in exile in Paris gave him a more encompassing and cosmopolitan outlook over what he vilified as Arguedas’s “parochial” and “telluric” writing. Arguedas furiously responded: “I am a provincial man of this world, who has learnt less from books than the differences that there are, and that I’ve felt and seen, between a cricket and a Quechua mayor.”

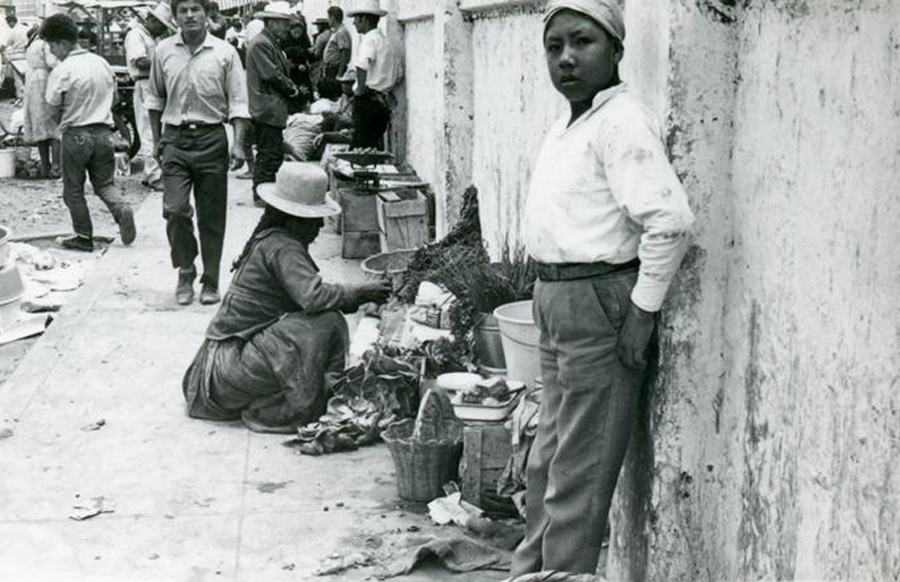

Like so many pioneers, often misunderstood in their own time, despite being characterised as ‘provincial,’ Arguedas was not anti-modern. His aim was to demolish what he described as the “isolating and oppressive walls” forced between the Quechua and Hispanic cultures, and focused on Quechua culture’s role in modernising Peru. In his final (and some say uncompleted) novel The Fox From Above and the Fox From Down Below published posthumously in 1971, Arguedas depicts the dystopian world of the Peruvian coastal city of Chimbote during the fishing boom in the 1970s with the arrival of mass migration from the Andes, which transformed Chimbote from a fishing village of 4000 people to an industrial mega-city with 30,000 people in three years.

Arguedas observed how the economic conditions effectively forced Quechua people to abandon their livelihoods in the Andes and move to the industrialising cities where their immersive relationship with nature was violently disrupted. He showed how capitalism plants the seeds for its own destruction, by creating a proletarian class out of the Quechua migrants. In the novel, Arguedas expands on Marx’s idea of capitalism itself as “a live monster that is fruitful and multiplies.” Arguedas shows how the capitalist monster-machine overfishing anchovies from the bay of Chimbote is fed rather than Mother Earth, with disastrous consequences as nature responds with an insurgent and equally violent force.

At the same time, rather than simply becoming “an appendage of the machine” (to cite Marx) he portrayed the migrants bringing their vibrant customs and beliefs with them in an act of resistance that creates a third space. Arguedas moves beyond binary metaphors of purity and contamination (whether of nature v.s. civilisation or of Indigenous cultures as opposed to Hispanic cultures) by showing the entangled assemblage of nature, industrialisation and social upheaval.

Arguedas expressed the near impossibility of treating nature as a subject in a system where the migrant’s survival is dependent on the cash nexus, and where ‘cheap’ nature goes hand in hand with cheap labour. Yet he explores the salvific potential of catastrophe expressed in the Quechua notion of Pachacuti, a social and geological catastrophe so destructive it provides revolutionary possibilities for a new world.

However optimistic his world view, reimagining disaster as a redemptive force to create a new equilibrium did not console his own sense of loss of the Andean world he loved from childhood. He was deeply traumatised by what he witnessed in Chimbote, and the novel, interspersed with his diary entries, ultimately deals with Arguedas’s own agonising existential crisis.

This internal crisis was too much to bear, but his work did have impact. In 1975, six years after Arguedas tragically committed suicide, the Peruvian government gave Quechua co-official status with Spanish, testament to his work.

Arguedas showed his readers a listening relationship and a non-anthropocentric stance towards nature in which we do not see ourselves as separate or superior to it. Rather than seeing nature’s generative qualities as something to exploit and its destructive ones as something to battle against, it becomes a connective space that generates feelings of belonging.

Listening to nature establishes a form of dialogue and communication that eliminates the boundaries of separation upheld by extractivist logic and the colonial legacy. The intellectual power of listening points to a way of perceiving the forces of the planet beyond human influence and timescales. In doing so, it enables the listener to become more human by becoming more sensitive both to our bodies and our senses and to what is within, around and beyond us.

In the case of Arguedas, listening to nature becomes a way to resist the coloniality of power and its historic exclusion of Quechua models of thought based on reciprocity and an animate nature. Arguedas elevated local Peruvian culture to a universal status and showed the ability of Quechua culture to adapt against the odds to new urban territories. These are important lessons we can learn from, adapt and listen to today.

In his Quechua worldview, civilisation could never fully separate nature from society – in fact he represents attempts to do so as a cataclysmic illusion that will be broken by nature’s insurgent capacity to reassert its voice with violence until we listen – the Quechua Pachacuti sentiment that nature is always deeply implicated in the catastrophes and creations that constitute our existence.

Arguedas’ work has a powerful resonance with the climate crisis and its root cause in how industrialised society relates to nature. Arguedas teaches us to revalue nature’s importance in society to inform a renovated cultural identity that points us towards a less anthropocentric-minded world.