The thought of a "Latin Lover" used to make me cringe. When I first arrived in Buenos Aires - the city whose Spanish-Italian ancestry makes for an almost caricatured machismo - I walked the streets both fascinated and terrified by the pastel shirts open to the bellybutton, long dark hair and arrogant smirks begging for a reaction.

I was appalled by the fact that I could not walk a block out of my house without receiving stares and comments illustrated by hand gestures which often verged on the theatrical. I say comments, but they ranged from flurries of romantic poetry (at least that was the impression on my limited Spanish), through chuckles of private amusement (occasionally shared with other male passers-by) to, most irritatingly of all, the mumble (doubtless too crude to share with anyone else at all).

It was not a question of trying to dodge that building site on the way to work. Every class of Buenos Aires society seemed imbued with the lascivious spirit of working-class Italy. Even professors at the university and colleagues at work, I was told, show little restraint. You don't have to be looking particularly wonderful to get what seems to be an automatic reaction. Once, rushing out to work at dawn, face puffed from sleep, clothes baggy and crumpled, scoffing down my breakfast in the most unattractive manner, a grinning passer-by stopped to tell me, as calmly as if he was asking the time, "I'd like to be that croissant you're eating." Was that a compliment, I wondered, or had I just been the butt of some joke?

I kept thinking how, in the oh-so-progressive north, this perpetual pestering of women would be swiftly condemned as a sort of mass harassment. But here in Argentina, I was merely the recipient of the piropos, the flirtatious remark from a passer-by that is as traditional to Argentines as eating beef. To give them their due, Argentine men do not appear to discriminate. Fat, thin, short, tall, young or old; in the piropo tradition, every woman is worth a comment.

"How do you bear being the objects of such scrutiny?" I would ask my Argentine friends, indignant at feeling increasingly self-conscious on the streets. "Oh, you get used to it. Don't you like the attention?" Fabiana, a local secretary replied, adding "I remember being in London and no man even looked at me. I started getting really insecure."

It came as no surprise to discover that fellow expatriates of the male sex were having the opposite problem with Argentine women. "For weeks, even months, Argentine girls expect you to shower them with compliments and treat them like they're God's gift before they'll give you the time of day," complained 24-year-old Chad, a student from New Jersey. Latin man, conversely, was possessive, insulting and oppressive, we gringos declared, and piropos were their tool of manipulation. If you can make a woman worry about the way she looks, she'll become dependent on male approval for her self-esteem.

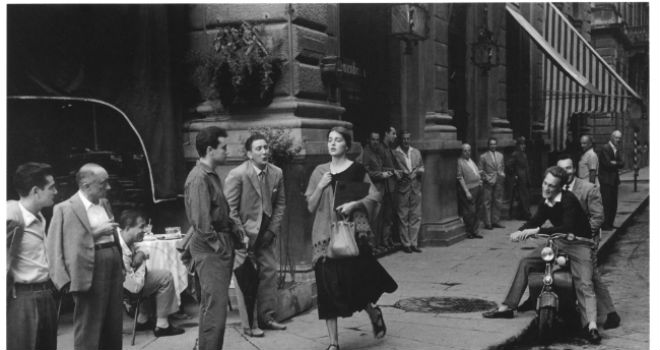

I gradually began to feel, however, that the fierce condemnations of Latin machismo were missing the point. I saw and admired how Argentine women floated through the crowded streets of Buenos Aires, treading proudly and defiantly through the minefield of scrutiny. Sometimes they permitted themselves a giggle when a piropo was too humorous to resist. And if the poet won a smile, his eyes would gleam with the pleasure of conquest, even though his prey was already disappearing into the distance.

As I became familiar with the language, I even started to appreciate their cocky creativity. "They never told me the sun came out at night," you might hear from a dark-shadowed doorway while on your night-time stroll, or "Oh, bon-bon, walk in the shade else all your sweetness will melt in the heat" on a scorching summer's day.

Dare I admit the warm sensation I felt walking the sidewalks of Buenos Aires? Quite unconsciously, I began to arrange my hair differently and to dress in a way which showed off my figure, hoping to invite some original verse. I revelled in those post-piropo moments, the tingling charge from the sheer nerve of the speaker, the flattering words still hanging in the air. I now realise that my initial misconception was to apply a European mindset to something I didn't understand. I discovered that before feeling threatened by comments directed at my sexuality, it was worth measuring the motives.

Not only did I learn something new about myself, but also about my mother, a feminist ranter and raver, who once lived here and still comes back to visit. On her last visit I finally decoded the little routine she carries out each time she comes: she puts her luggage down in my apartment, changes into her green and yellow mini-dress and, in all her voluptuous glory, sets off to walk the streets of Buenos Aires alone. It can only be one craving she is going out to satisfy- that for the Argentine piropo. I'm sure some day I'll be back for it, too.