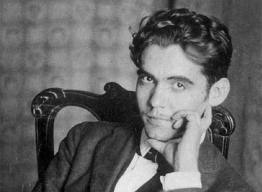

Some of the most important Arab poets of the twentieth century have paid homage to and evoked the memory of the Andalucian Poet Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936). They include the Iraqi poets Badre Shakir al-Sayyab (1926-1964) and Abd Al-Wahab Al-Bayati (1926-1999), the Egyptian poet Salah Abd Al-Sabour (1931-1981) and the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008).Their poems are a testament to Lorca’s genius and far-reaching scope of insights that touched people and poets on a profound level. At heart, Lorca is a symbol of passion, defiance to oppression and a champion of freedom. He is particularly special to the Arabs for this, as well as for his unique vision of Andalucía as a tolerant fusion of cultures and civilisations.

Besides the vivid homage of the Arab poets to Lorca, there are clear traces and influences of Lorca’s poetry in their work. But Lorca’s influence on Arab poets was not unreciprocated. There is a cycle of poetic migrations which connect Lorca to the Arabic tradition in notable and exciting ways. This is particularly evident in Lorca’s great poetry collection, 'The Gypsy Ballads', which he published in 1928, catapulting him to further fame and admiration. Moreover, Lorca’s poetry continues to influence and be echoed in modern Arab poetry until today, including the great Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, whose poetry exudes with metaphors similar to Lorca, olive trees, besieged creatures, gypsies, and lovers and beloved.

Spanish and Arab brothers in poetry

Lorca and Darwish both lived through turbulent times, which influenced their poetic vision. In an early poem entitled “Lorca”, Darwish addresses Lorca directly:

Forgetfulness has forgotten to walk on your radiant blood

So the roses of the moon were drenched in blood

The noblest of swords is a letter from your mouth

About the songs of the gypsies

'The Gypsy Ballads' is anchored in Andalucía and is a superb continuation of an important Spanish ballad tradition dating back to the renaissance. But what adds to the sensual distinction and visionary lyrical quality of the poems is the diversity of the influences that feed and emanate from them, influences which translate Lorca’s vision of Andalucía as a diverse seat of civilisations.

Lorca himself describes one strand of these influences as follows: “From the very first line [of the Gypsy Ballad] we note that the myth is mixed with what we might call the “realistic” element. But, in fact, when this “realism” touches the plane of magic it becomes as mysterious and indecipherable as the Andalusian soul, which is a dramatic struggle between the poison of the Orient and the geometry and equilibrium imposed by Roman and Andalusian civilisations.”

Lorca’s interaction and dialogue with the Arabic tradition appears in his great poem Romance Sonámbulo ('Dreamwalker Ballad'), where he declares repeatedly:

Pero yo ya no soy yo

Ni mi casa es ya mi casa

These two lines of “I am no longer who I am, nor is my house my house” have an interesting history of migration starting with the great 9th century Arab poet Abu Tammam to the 12th century Ibn Khafaja in his elegiac ode to the fall of Valencia when the El çid conquered it, even though in the original Arabic, it appears as “you are not you, and the abodes are not abodes”.

These lines, which Lorca echoes, represent a well-known sentiment in classical Arabic poetry that evokes loss and psychological unsettlement, loss of a place, or change in the order of the place or the country which engenders disorientation, hence cries of longing and nostalgia for a semblance of stability and settlement, emotions with which the poetry of Lorca brims:

Compadre, quiero cambiar (friend, I wish to trade

Mi caballo por su casa, my horse for your house

Mi montura por su espejo, my saddle for your mirror

Mi cuchillo por su manta. My knife for your blanket)

There are several interpretations to this most famous of Lorca’s poems, Romance Sonámbulo, which he considered his greatest. And though it is difficult to settle on any one interpretation, the voices of rebellion against the then existing social and political order ring clear. It is a cry for freedom, of expression and behaviour and from institutional or social repression. Though there is focus on the sexual dimensions of the poem, there are political hints in it that make it diverse in its meanings and effects:

Drunkard Civil Guards

Beat at the door.

Green how I Love you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

Boat on the sea,

And horse on the mountain.

Here we are confronted with the image of the Spanish civil guards disrupting the simple lives of the gypsies. Followed with seeds of hope, green wind and branches, the sea is befriended, and the mountain is surmounted. As if green speaks for a ripened, responsible freedom, freedom that leads to openness, possibilities, which the gypsies represent, beyond that which the civil guards could understand in their regimented structures. It is integral to the desire for freedom which is inherent in all great poetry.

But the poem has a lyrical dimension which, irrespective of the meaning, is assured. In its very lyrical, mystical quality, it establishes houses of visions from within the language, places of liberation and ascendance, in the seemingly disjointed structure of the poem.

Lorca drifts East

The beautiful opening line of the Romance Sonámbulo “Verde que te quiero verde” migrates in notable fashion to the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s epic poem, “The Dice Player.” Like Lorca, Darwish’s late style in poetry, is one of rupturing and opening spaces, while deepening bonds between people and land, between voices and souls, between lived experiences, consciousness and dreams, reality and imagination — an inspired message to individuals to rise above pettiness and provincialism and realise the wholesomeness of their being. It is also characteristically open to expansive interpretations, the way Lorca’s great poem is.

‘Green, O land, how I love you green

An apple, waving in light and water. Green. Your night Green. Your dawn green. So plant me gently, with a mother’s kindness, in a fistful of air.

I am one of your seeds, green…’

Greenness is what unites those two poets whose openness and defence of life comes to life with this eternal signature of life. They also share similar symbols and references, as they evoke similar historical memories of injustice in the face of harsh political and emotional repression. In what follows is Lorca in the Book of Poems, calling at Jesus to give him the childhood he once had:

I will say to Christ,

Lord, give me the child’s soul I once had.

And in what follows is Darwish in his long poem A State of Siege, written in the wake of the Israeli siege to Ramallah and other cities in the West Bank in 2002, evoking Jesus’s outcry on the cross, as narrated in the Christian tradition:

My God, My God,

Why have you forsaken me!

While I am still a child

And yet to be tested?

Meanwhile, notice the lyrical motion inherent in the poems, the symbols and visions that render language a free world in its own right. But it is not all about life in Lorca’s poetry, as passion and death preside over much of what he wrote. Hence many interpretations have paid attention to the themes of death and passion in his ‘Gypsy Ballads’:

Friend, I want to die

Tucked up in my bed:

A steel bed, if possible,

With the finest linen sheets

It is perhaps no coincidence that the last works of Mahmoud Darwish are also devoted or concerned with death, domesticating death, making it less of an another world. Lorca’s poetry is overshadowed with desires about a particular type of death, obviously a peaceful one, as he wants to die in his bed. But unfortunately, his fate was one of the cruellest, taken away from the peace of his home by the ultra-nationalists in Spain and executed three days later following his arrest in his beloved Granada in August 1936.

An inspiring legacy of defiance

What Lorca has done in his relatively short, but eventful life, confirms his passionate engagement with the causes of his time, even though he tried to shy away from demonstrating a particular partisan inclination. His poetry remains a testimony to a time of oppression and fear, defied and surpassed by sensitive aesthetics which he championed and have migrated into various traditions, notably the Arabic one. After all, Lorca was a defender of the assured place of the Arabs in his native Andalucía, describing in the year of his assassination, 1936, their expulsion in 1492 as, “un momento malísimo…se perdieron una civilización admirable, una poesia…una arquitectura y una delicadeza únicas en el mundo”. At a time of great upheaval and revolutionary hope in the Arab world, Lorca serves as a passionate voice for freedom and liberation from multiple sources of oppression:

Verde que te quiero verde

Verde viento, verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

Y el caballo en la montaña

On a personal note, I read several Spanish-speaking writers and poets before I stumbled upon Lorca. In him I found an extraordinary talent which brims with vitality and sensuousness that feeds the brain and the body with sheer wonder. When I visited Spain and Granada for the first time this year, that magically tender place, which Lorca made vivid as the jewel of the Andalucía in his poetry, I identified with Lorca’s metaphors and emotions. I felt inspired by his presence to follow in his footsteps and sing for Andalucía.

For this part of Spain, of the world, inspires singing: What could one do in paradise except sing and meditate, make companions of its objects, its verdant landscape, its running water, its steadfast stones, warm moon and sun, embracing a delightful patch of this mysterious earth, called Andalucía with its capital, Granada of the heart, and Lorca, one of its great eternal seeds. But more than that, it invites hope and optimism to think of Lorca and Granada, a place in a figure who cried out for an Andalucía, ripe in its ideals of freedom, justice and tolerance.

The launch of the new English edition of 'The Gypsy Ballads' will take place on 29th September @ Kings Place. Click for more info