There is something incredibly refreshing about entering the world of Mira Schendel’s artwork. I use the word refreshing because I cannot help but feel that through her work she gets to the bare bones of a very human quest. The sheer variety of Schendel’s work is often mentioned, for she experimented with different mediums. It is impossible to neatly box her with a particular movement or ethos. Whilst it is interesting and very useful to draw connections between Schendel and her contemporaries, it would be futile to try and attach her to a precise manifesto of aesthetic criteria. The variety, questioning, self-reflexivity and fragility of her work provoke important questions in powerful but also playful ways.

Born in Zurich in 1919, Mira spent her childhood growing up in Milan. As a Jew at risk of persecution under the fascist regime, Mira was forced to flee Italy and moved to Porto Alegre in 1949 with her first husband before settling in Sao Paulo with her second husband, Knut Schendel in 1953 where she surrounded herself with a select group of philosophers, poets and physicists. She remained in Sao Paulo until her death in 1988. As with many portrayals of the artist, Mira has been captured as an ‘outsider’ figure, the intellectual with a volatile character who kept a small circle of friends and confidants. The geographical dislocation that she physically experienced echoes the jumps and starts in her work- the flux between different styles and techniques which provide a rich and intricate story of multiple voices.

This exhibition at Tate (25th September-19th January) is an important exhibition, not only the first international retrospective to showcase the work of the artist, but also the first solo exhibition of her work for over a decade. More recently, Schendel’s work was displayed alongside the work of Argentinean artist Leon Ferrari in Tangled Alphabets at MOMA (2009), an exhibition which explored the interesting painterly quality given to text within the image that both artists are famous for. This exhibition stands as a significant example of Tate’s attempt to bring art produced outside of Europe and North America into the spotlight- a move encouraged by strong currents in Art History and Theory since the sixties to cultivate a documentation of art practice from around the world in opposition to the traditional hegemonic and ethnocentric tendencies that for many years dictated who and what should be considered within the realm of ‘Art.’

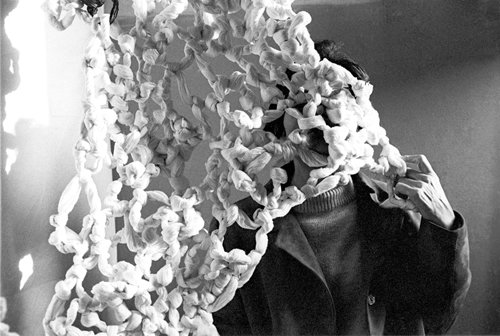

This photograph above of Mira Schendel taken by Clay Perry evokes some of the thoughts that come to mind when glimpsing particular works by the artist. The photograph is at once playful and dark, vulnerable and strong, intimate yet distant and somehow telling whilst simultaneously poised to confuse. Such dialectics are prevalent in the intricacies of the objects themselves- objects, which, as an extension of the artist, emit different stories to different viewers. In Perry’s photograph, Mira conceals her face with one of her Droguinhas or Little Nothings from the mid-sixties- interwoven, fleshy forms made from Japanese paper.

The Untitled work (shown in the youtube clip below) from the series Droguinhas (Little Nothings)' 1964-66 (www.moma.org)suggests a kind of devaluing of the art object itself and perhaps a nod to the superficiality at the heart of an elitist art world- a common message in avant-garde practice. We are also reminded of other artists working in Brazil at that time. Artists such as Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Helio Oticica viewed under the Neo-Concrete movement in Brazilian art. Art ought to be participatory and envelop the viewer in such a way that they were as much a part of the work as the artist. Critic, poet and champion of Neoconcretism, Ferreira Gullar, wrote of the ‘non-object’ in 1959 suggesting that such works of art by the group were unclassifiable as a particular medium and therefore the viewer was free to perceive them without any conscious preconceptions. The viewer was supposed to experience the object via the senses. While Schendel is not directly seen as a member of the Neoconcretist wave, a work like this one from the Droguinha series plays on bodily movement, entering the space of the viewer as if inviting us to become entangled in the unidentified web like the photograph taken by Perry of the artist herself.

The exhibition at Tate will showcase Mira Schendel’s Monotype series, which consists of a vast array of beautiful oil on rice paper drawings. Schendel made in excess of 2000 of these Monotype works or Monotipia between 1964 and the late sixties. These fragments of Japanese paper on inked pieces of glass with talcum powder were written into by the artist using either a sharp tool or her fingers. The images can be seen from both sides, offering multiple points of visibility, a detail which seems to mirror the highly subjective nature of writing, dialogue and other forms of communication. Schendel seems to create a space that is left open for multiple interpretations.

There is a sensual, even painterly approach to language in Mira’s work. Language is nonsensical in terms of lexical meaning, as each letter floats freely in topsy-turvy formats. Like stencils you want to fill in, or magnetic letters on a fridge, you can’t help but want to rearrange them and communicate by playing. Boundaries between language and image are blurred here. Schendel’s work, perhaps like all worthwhile art, questions us and potentially leaves us feeling momentarily displaced. Letrasets are associated with a standardization of typography and design- but in Mira Schendel’s worlds they are shaken, spun, warped and made to hover. The usual codes of communication do not apply. The exhibition at Tate is a wonderful opportunity to get a glimpse of the complex mind and soul of an artist whose work has until now been little displayed in the UK.

See the exhibition: http://www.tate.org.uk/about/press-office/press-releases/mira-schendel-1

Image