Jessica Sarah Rinland is not your usual documentarist. She observes the minutiae, the intricate, the normally unobserved. With long sequences in tight close-up, Rinland conveys the experience of being a part of a zoo, with interactions between species, either as a worker, an historian or between the animals themselves. Creating a multi-layered soundscape, she expands into something more than what we are perceiving on a visual level. This is Rinland’s second feature, and although it delves into the history and architecture of the Buenos Aires Zoo and the dedicated persons that care for the animals, the film remains on a level that is unusual for a documentary. There are questions left hanging and there is a sensory element that opens unexpected doors. We are used to film involving animals having a narrative, à la Attenborough, here there is no obvious story being told. It suspends time, seemingly asking the viewer to experience the moment. No more, no less.

Jessica Sarah Rinland

Jessica Sarah Rinland

Rinland, as cinematographer, with her 16mm camera, “navigates spaces where culture and nature meet.” She endeavours to convey the atmosphere, the spiritual element, the relationships of the carers with their wards, as well as the effort being made to restore the stunning architectural buildings of the Buenos Aires Zoo, while they care for rescue animals that can no longer be rewilded.

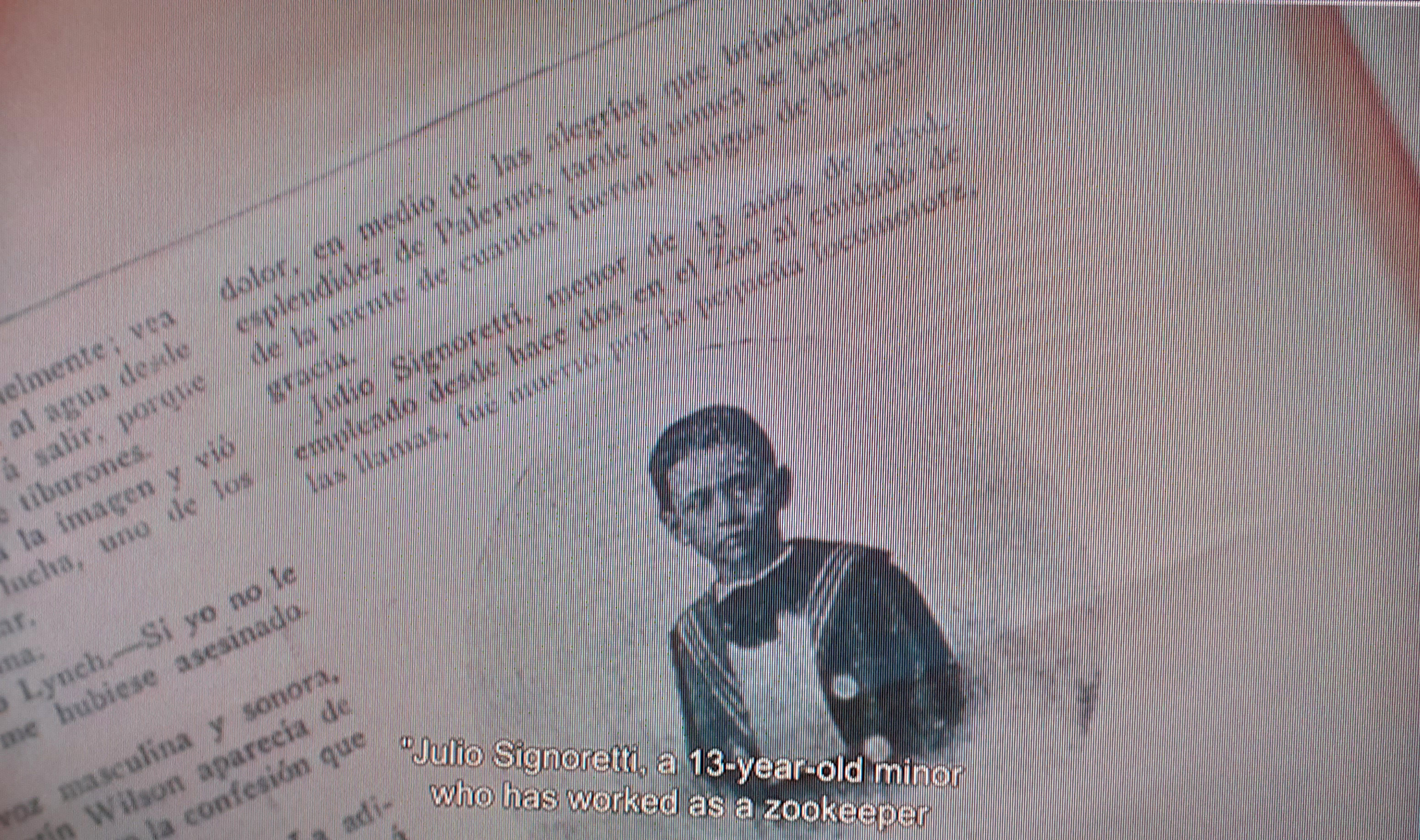

With a large tattoo of the South American continent on her back, Maca (Macarena Santa Maria Lloydi) goes about her work in the zoo, talking non- stop to her charges with enormous affection. In a particularly moving scene, she warmly embraces and talks to Juanita, a frail and dying monkey, (that, sadly, died only a week after filming ended). Maca is accompanied on her rounds by Alicia Delgado, while Majo (Maria Jose Micale) works on the history of the place, restoring and rebinding the old 19th century zoo magazines, and conveying some of the magic to the visitors in her tours. It was a delight, therefore, to have the chance to chat with writer / director Jessica Sarah Rinland at the 2024 BFI London Film Festival.

“I think that because I studied Fine Art [Central St Martins UK], I started making films after I became interested in photography and painting. I am very interested in music and sound as well, so film, in a way, encapsulates a lot of the things that I was interested in separately. It allows me to explore literature, writing, image making, sound, and editing, in a great way, so that is why I think it is a great medium and also there is the experience of ‘collective watching’ which is very special to me.”

A veteran of a number of successful shorts, Rinland’s films have a quirky, right-brain character, with some surrealistic subject matter like in NULEPSY (2011) where she questions what life would be like without clothes, or NOT AS OLD AS THE TREES (2014) where an old man, curious about how the world looks from the top of a tree, spends his time climbing them.

Elephant presenting its foot for a much enjoyed pedicure

Her use of soundscape layers as part of the narrative, is one of the elements that stands out in ‘Collective Monologues’, and at times, can be, not only effective, but even disturbing: -

“In my previous films, I, mostly, did not use a lot of sync sound, so this was one of the first films in a while that we recorded sync sound. For ten years now, I have worked with the same sound designer, Philippe Ciompi. [In Argentina] I was working with Guido Ronconi, the Argentinian sound recordist and then, in London, I did the post- production with Philippe. I was sending Philippe messages as I received the footage. As I was syncing, I was thinking: “My god, this is incredible. It is such a basic thing but it was incredible having the sync sound and what that does to the film”, but Philippe wrote me a message saying: Remember, don’t get zessed with the sync sound, remember what we can do with sound that is not there already, and how much we can bring in. That is something Philippe and I work on a lot, the construction of sound, especially with the close- ups. Something that I love with the close-up is that sound creates a space, so you can imagine the rest of it, [like] when Maca is with Juanita without needing to see it, because the sound creates it.

You can hear something like an ambulance in the background or the road, so you know how it is situated in space. With Philippe that was really important, whenever we work together, I know pretty much what I would like, it’s always a conversation and a collaboration, but there is always one part of the film which I leave up to him. In this case, it was the 4-minutes sequence of the elephants walking out of the Hindu temple and he constructed this sound in which you can hear details of elephant’s actions, like picking up a branch, but then, you can also hear the cars that are going past. We thought a lot about the hum of the cars because, as you know, [the zoo] is right next to Plaza Italia which is very loud. So then, the idea of cars going in and out, creates more of a sound for the audience, because of the contrast between silence and loud sound.

There is also a sequence where there is construction [work] going on with a camel, which was something we also wanted to heighten. This idea of the contrast of the loud noises and, as what Majo was saying [to the visitors] about [Wednesdays] being a Day of Rest, with the animals not hearing much sound. So, it’s like the contrast between what she is explaining about the zoo and what is actually happening there. It is subtle, I do not use a Voice Over, but there is a heightened sound that allows you to experience that.”

Flamingos getting ready to be re-wilded

Flamingos getting ready to be re-wilded

Other sensorial elements in the film are also emphasized by Majo, the Zoo historian. In one scene, she reads out a section of the annotated observations of the zoo’s second director, Clemente Onelli, who ran it from 1904 till he died in 1924. He lived in the zoo with his family and enjoyed touring the grounds taking notes, in this case, with a relevance to smells: -

“The Asian elephant, despite being so huge, does not emit any odour, neither from its breath nor its pores. His dung, compared with that of a horse, is almost odourless, [while] their urine has a slight musky smell. If we now pass to the area of the bears, in their well-ventilated palace within a huge courtyard, although weak, it has a unique, nauseating smell of rotting meat that has been left in water for hours. Some of these seems to emanated from glands on the soles of their feet.”

Alicia Delgado and Majo ( María José Micale) discuss administration issues.

Jessica: -

“I was living [in Buenos Aires] on República de la India, which is one of the streets that overlook the zoo. Friends and people who had lived there, mentioned to me that previously (not nowadays). you could smell the zoo from the balconies. That’s something that always stuck in my mind, and when I was doing research with Majo, on the magazines, I came across this text by the second director Clemente Onelli. Majo had already done lots of research on him and knew a lot about him. She was restoring his books in the zoo and when I read this text about smells, it really kind of exploded. As humans we always classify things by vision by the way that we see, so it was very important to me to include other senses like touch, hearing and smell… the incredible detail that Onelli goes through while he’s visiting and touring around the zoo with the smells, the adjectives that he’s using and the details of the [scent glands] in the feet of the bears is incredible.”

In similar fine detail, Rinland points out how they are now finally restoring the original architecture of the Buenos Aires Zoo. Impressive to this day, it is something people never forget. It was designed by the Zoo founder, Eduardo Ladislao Holmberg, who was the director from 1888 till 1903, till he was fired for having fiery political differences with President General Roca and the local mayor. Some of these buildings are almost like follies, but their structure and character was designed so that the visitors could immediately identify the animal’s country of origin. For instance, among the most distinctive is the Hindu temple that houses the elephants, likewise the Egyptian inspired enclosure for the moneys.

Restoring the temple

However, Rinland explains that the state of the Buenos Aires Zoo gradually deteriorated over the 20th Century: -

“The zoo closed in 2016 to 2019 because of animal’s rights protests and also because the zoo carers protested. They were both fighting for animal rights and the horrible condition that the zoo was in.”

When it reopened in 2019, it was as an Eco-Park, with the intention of creating a sustainable system with an emphasis on conservation and environmental issues. With long close-up sequences of hands working on sculptures and plaster details, Rinland films the restoration of these magnificent, crumbling buildings to an encompassing soundscape in the background.

In the end, however, what remains with the viewer are the moving interactions between the keepers and their charges. In particular, Maca spending quality time with Juanita, the affectionate sick monkey, or working with her colleague Alicia, trying to teach two rescued Macaws how to fly, so they can be rewilded. (But sadly, after so many years in captivity, Ipi and Tesai, failed to learn and will have to spend their lives at the zoo).

“The film is called Collective Monologue which is a phrase that Jean Piaget (1936) coined, which is about a moment in time in a kid’s life between 2 and 4 years old, around then, where they sit in a circle and are always speaking but they don’t listen. They don’t have the tools to be able to listen yet, [as] they haven’t developed it yet. He called that a ‘collective monologue’ and in the way that he described the phrase, he says “children of that age are ego centric, but they also believe that nature was created for them… I was having a coffee with a cousin of mine in La Plata, Argentina in 2020 and I was telling her about the film …and she mentioned Piaget the psychologist- immediately I thought that was the title of the film.”

This film which premiered in Locarno 2024 received a Special Mention there and won awards at the San Sebastian Film Festival, Best Film at Documenta,Madrid, Primer Premio at BIM (Bienale de Imagen en Movimiento Buenos Aires), Arts + Science Award at Ann Arbor Film Festival, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Schnitzer prize for excellence in the arts in 2017.

‘Collective Monologues’ is to be screened again in 2026

BFI SOUTHBANK LONDON (+Q&A) - 19 February - 18:10

ICA LONDON (+Q&A) - 21 February - 18:00

PHOENIX LONDON (+Q&A) - 28 February - 14:00

PICTUREVILLE BRADFORD - 1 March - 14:00

CINE LUMIERE - 7 March - 18:00

COLLECTIVE MONOLOGUE (2024)

Director, Cinematographer and editor: Jessica Sarah Rinland.

Production: Melanie Schapiro and Jessica Sarah Rinland/ Sound Designer: Philippe Ciompi / Direct Sound: Guido Ronconi / Camera Assistant: Florencia Labat / Music: Los Hermanos Cuestas/ Foley: Jessica Sarah Rinland.

Cast: Macarena Santa María Lloydi / María José Micale / Alicia Delgado/ Juanita , the monkey.