Gilberto Gil was the first musician I ever saw on stage. I was eight years old and I remember a lot of legs (my eyes only meeting hips), long hair and ponchos in the packed Palais of Hammersmith. The poetic significance of bringing my own six year old son to see Gilberto Gil at the Back2Black Festival last month, and it being his first ever concert, didn’t dawn on me until I saw the unmistakably elegant figure of Gil at the other end of the press room, almost identical to that of 30 years ago but for the black hair now grey.

Having left my son downstairs (accompanied I hasten to add) I was hurried upstairs, totally unprepared for being face to face with this Brazilian legend and my first ever musical experience, who has left such a mark on my musical taste.

I encroached sheepishly as Gil talked to Brazilian journalists. What struck me most was an openness, an interest and eagerness to talk, a willingness to give thoughtful answers, and a respect for these journalists, in effect strangers whom he had no obligation to talk to. This was the most surprising; when most famous people at best tolerate the media (at worst show contempt), the procedure appeared to be no bother at all to Gil. He looked at us all, in the eyes, inquisitively, encouragingly.

“Where was that concert?” he asked, when I got the chance to tell Gil of this significant and serendipitous moment for me.

“Hammersmith Palais” I replied.

“Ah yes” he remembered, wide eyed and smiling, not like an old man reminiscing but in an alert, instant kind of way, as if it were last week. “I remember it. That must have been in ‘83, almost 30 years ago!”

Another striking thing: youth. Although greyer, he has maintained that slight, healthy build and he looks almost pure, childlike, as if still charmed and excited by the world. He liked the idea of my son:

“The circle of life!” he exclaimed and, smiling, asks, “And what is your name?”

Despite his years and his fame, there is nothing taken for granted. The antithesis of cynical, there is an essence to Gil that one can only describe as deep humanity. Perhaps it’s due to his years of macrobiotic vegetarian diet and meditation. They certainly haven’t done him harm, and listening to him later, I was amazed at how pure the voice of a 70-year-old could be. You realise what a feat this is when you hear how great voices such as Hector Lavoe’s, Frankie Ruiz’s or even George Michael’s can become irrecognizably hoarse and grainy, after years of smoking or drinking.

You are such an inspiration one journalist asks him, what advice can you give to young people?

“Well the main thing, is that I’ve always felt I’ve been in the best place I could be. I think you have to try to live right by yourself, be true to yourself, both personally and also in relation to those around you.”

Would the ‘best place’ include, I wondered, that night in February 1969, when a young though already famous Gil was arrested by the recently arrived Brazilian military government and, along with fellow musician Caetano Veloso, spent three months in prison and another four under house arrest, before being freed on the condition that they leave the country. They were allowed to play one last concert to raise funds for their plane tickets, before flying from fame to obscurity in Europe.

Of course, he says, he was in the right place. He was just doing, being what he was, a musician, it just so happened that his music, "represented a threat, something new, something that can't quite be understood by the authorities who had a different idea of culture. That was dangerous."

If Gil hadn’t have been made to leave, he may never have known Europe and London, where he decided to settle with Veloso. “We started in Portugal and then moved to Paris, but we didn’t really feel at home there. So we moved to London, and decided that this was the right place to be for us,” Gil says. “It is an experience that I remember with a lot of affection. I had a lot of respect for English music scene, and the fusion of the arts and creativity in that hippie era in general. If we had to be outside Brazil, London gave us a kind of freedom that was reassuring.”

Was London in the 60s really free? I asked

“Free? Well they called it Swinging London, but it’s a lot more swinging now! Back then it was still coming out of the shadows of the post-war era. But what was clear was that there was a hunger and search for freedom in people and this was given space and expression to breathe.”

Gil and Veloso took a house in Chelsea, sharing it with their manager and wives. Veloso in particular was very homesick and, despite being the hippie era, the English are well, English. “I was a foreigner, I didn’t come from the colonies so there was no connection with Englishness, I didn’t speak the language, wasn’t familiar with the culture, and didn’t understand their customs.”

At the same time Gil and Veloso got involved with artists who appreciated their talents. Few people know that Gil helped organised the first Glastonbury in 1971, chewing over the logistics of what is now the UK’s biggest festival, and musing over how its should follow the Brazilian Carnival model – open and wild. London also exposed Gil to Reggae, which was to have a huge influence on his music. Gil met Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff and his rendition of No Woman No Cry in Brazilian Portuguese is probably one of the best there is. It is the song that I most remember from that concert I went to as a child, his first return to London a decade after living. It went straight through me, electrifying my little still-stretching bones

Both Gil and Veloso were also heavily influenced by the rock and psychedelia scene, performing with Yes, Pink Floyd, and The Incredible String Band. Even the surrealism of Monty Python's Flying Circus, Veloso has said, influenced some of his more experimental music. All these influences together combined with his own deep authenticity, confidence in his own roots, and amazing song writing are what gives Gilberto Gil’s own distinctive style found of tracks such as Tenho Sed and Menina Baiana.

In the press conference we still follow the theme of freedom. One Brazilian journalist asks if Gil ever thought the English took things too far with their liberalism and excesses.

“I’m not scared of excesses, one shouldn’t be scared of excesses,” Gil replies philosophically, with the calmness of a politician. ”Infact I believe excesses are necessary. Excesses are a natural and important part of life’s process. You need to have excesses to find your balance. And in the case of the UK, it is the out of control-ness that have produced some of its most succesful artistic expressions, exported to the rest of the world and is a source of income for it. So, even on an economic level it can be justified.”

And what about Brazilian music, asked one journalist, why are Brazilian musicians less well known in the world?

“Unfortunately, in the past a lot of musicians have to leave their country in order to make a living. But things have changed a lot in music, it has become decentralised in this post-internet culture and people from everywhere are getting plugged into music from the other side of the planet. A few years ago I played at a festival in Finland, which was dedicated exclusively to funky carioca music. So music is now able to trans board culture and nationality in a way it couldn’t before.”

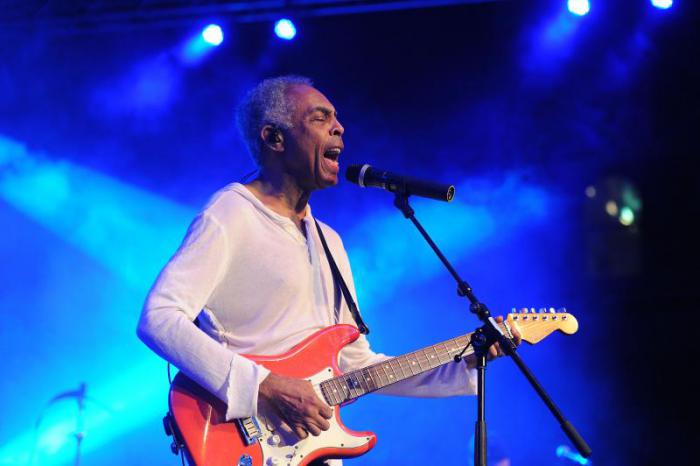

What Gil’s humility doesn’t allow him to say is that, in his own case, it is a uniqueness, versatility and ageless universality that have allowed him to trans board as an artist. No better example of this magic was seeing him at his two performances in London. Hours after our press conference, I joined my son to see this seventy-year-old rocking the crowd in the old Billingsgate Market, looking so fresh he could have just hatched out of an egg. He was like Mick Jagger, after a year’s retreat in Tibet. He played No Woman No Cry transmitting the same simplicity and authenticity that made such an impact on me as a child.

Two days later at the Barbican, Gil fronted the London Symphony Orchestra in sandals, linen shirts and trousers, in a collaboration that could have been a disaster. Yet, aided by the incredible arrangements of great Brazilian composer and arranger Jaques Morelenbaum, with whom Gil sang a song accompanied simply by Morelenbaum on cello, the combination of rich orchestral musicality and Gil’s simplicity was enough to raise hairs on the back of your neck. By the end, even the philharmonic musicians themselves looked mesmerised and completely under the spell of the beauty and innocence emanating from Gil

On both occasions, true to his own philosophy, Gil looked precisely in “the best place he could be.” It was that simple.