In 2018, the then Secretary General of Amnesty International, Salil Shetty, warned that political polarization, economic decline and an increasing disillusionment with democracy had led to a crisis of human rights in Latin America. “Latin America was always seen as more advanced in the area of human rights compared to Asia or Africa, but everything has gone backwards very quickly now,” he said.

In this context, the brave work of all the activists, leaders of social movements and human rights defenders across the region has become more vital than ever – but also more dangerous. The assassination last year of Rio de Janeiro city councillor Marielle Franco shocked the world, but the reality is that human rights, land and environment defenders are being killed regularly across Latin America without making the headlines. And yet, despite the danger, people continue to resist.

These include Ana Paula Oliveira, a human rights activist from the Manguinhos favela in Rio de Janeiro, who has fought for human rights and against state violence since 2014, when an officer from the local Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) shot dead her son. Along with other mothers from the favela who have also lost children to police violence, Ana Paula founded the group Mães de Manguinhos (Mothers of Manguinhos), which provides support for families and fights for justice for the victims. Thanks to Ana Paula’s persistence, the Rio de Janeiro courts decided last year that the officer responsible for her son’s death will face a jury trial – something extremely rare in these cases. In the current context, in which Brazil’s president has said that “Police who don’t kill aren’t proper police”, the commitment and courage of Ana Paula and the other women of Mães de Manguinhos are all the more critical.

Ana Paula Oliveira

Ana Paula Oliveira

Their fight is not just a legal battle for justice for their children, but a cultural one. They are up against deeply ingrained racism, classism and punitive attitudes towards criminal justice. As Ana Paula says, “It’s all the prejudice, all the racism that is rooted in society, in the whole system, the judiciary, the media. Every time we can talk, we scream, and tell our story of pain and struggle. And I’m sure that at least one person will be moved by what we say, when perhaps before they had thought of everyone in the favelas as poor black criminals who deserve to die. When a mother speaks about her struggle, even if this has an impact on just one person, things begin to change. People begin to reflect on their beliefs. That’s why I think it’s so important for us to speak out.”

Another remarkable story is that of Camila Méndez, a young Colombian environmental activist from Cajamarca, in the department of Tolima. Camila participated in a campaign to hold a consulta popular – a kind of local referendum – on the installation of the La Colosa gold mine near her town by the South African company AngloGold Ashanti, the third-largest gold mining company in the world. Thanks to the hard work of Camila and her group, the Cajamarca Socioenvironmental Youth Collective (COSAJUCA), and other local organizations, the people of Cajamarca successfully resisted pressure from the company and both the local and national governments, as well as threats from paramilitary groups active in the region.

The consulta popular was held in March 2017 and the result was decisive: 98% of voters rejected the mine. AngloGold Ashanti – which invested $900 million in Colombia between 2006 and 2017 and had been doing exploration work for La Colosa for 14 years – was forced to recognise the result and withdrew from Cajamarca a month later. As Camila says, “Cajamarca has become a beacon of hope (…) Once we had achieved it and shown that we, a campesino community, proud of who we are but with limited resources, really could confront this monster, one of the world’s biggest gold producers – that fills people with hope.”

Camila Méndez

Camila Méndez

Other positive stories include that of Edgardo Fernández, a veteran LGBT rights activist and tango teacher who has helped bring about radical change to Argentina. He dances queer tango, which is, in his own words, “a different way of teaching, learning, dancing, and behaving in the realm of tango”, in which, unlike in traditional tango, women may ask men to dance, and of course, same-sex pairs are possible. “Why did I choose tango?” he says. “I’ve been an activist in gay rights organizations for 33 years, since the end of the last dictatorship here. I saw an opportunity to use tango to do something different. I saw that nobody was using dance to try and effect social and political change anywhere, and I had the idea of using dance to try and send messages.”

Edgardo uses tango events and flash mobs to campaign not only on LGBT issues, but also on violence against women and mistreatment of the elderly. He began his career as an activist back in the 1980s when the Argentine LGBT community was routinely harassed by police; today, Argentina has some of the most advanced LGBT rights legislation in the world.

Edgardo Fernández

Edgardo Fernández

The Mexican urban mobility and road safety activist Jorge Cáñez is another who brings a spirit of creativity and irreverence to his activism. Jorge has an alter ego, Peatónito (a play on the Spanish words peatón, pedestrian; and atónito, astonished) who takes to the mean streets of Mexico City dressed as a lucha libre fighter to defend the rights of pedestrians. Peatónito’s activities include pushing cars back where they have blocked crossings; helping pedestrians to cross roads safely; painting pavements and zebra crossings where they don’t exist; and most controversially, walking over cars where they have parked illegally on the pavement. As Jorge says, “We took the atmosphere of the ring, the spectacle, onto the streets, where the battle is for a better city. It’s a fight to protect pedestrians, reduce the number of casualties on the roads, and start constructing the city on a more human scale.”

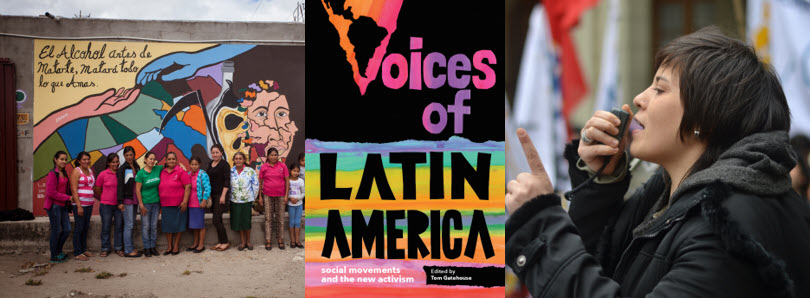

The new title Voices of Latin America, from the independent publishing house Latin America Bureau (LAB), brings together the stories of these activists, alongside those of around 70 others, across 14 different countries, from Mexico to the Southern Cone. All show that however worrying the current social and political scenario may appear, the resistance is very much alive and well.

Voices was published in January 2019 and should become a key reference for anyone interested in social movements and the new activism in Latin America. For your copy visit https://developmentbookshop.com/voices-of-latin-america and for more information visit http://www.lab.org.uk/voices