In 2002 I spent a year as a field volunteer in Colombia for Peace Brigades International (PBI), an organization which provides protective physical accompaniment to Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) in conflict zones. Most of the HRDs we accompanied were individuals: lawyers investigating massacres; women organizing in shanty towns; families of the detained and disappeared visiting prisons or attending court.

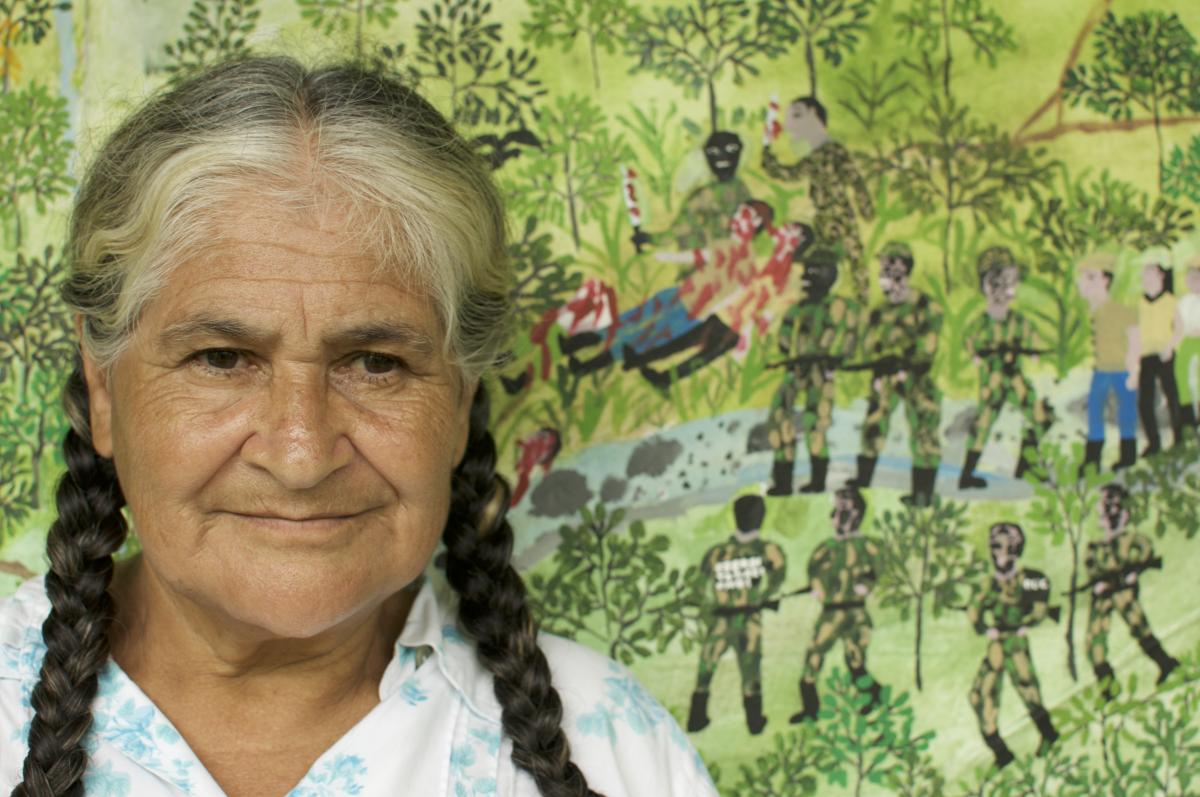

But we also accompanied several rural communities, victims of waves of atrocities and repeated forced displacement in the epicentres of the 50-year long Colombian civil war. In the heightened violence of the mid-1990s, they had declared themselves Peace Communities, a neutral space that did not allow armed actors – guerrillas, paramilitaries, or the Colombian army – onto their land.

The most emblematic of these Peace Communities is San José de Apartadó (SJA), a small settlement of campesinos within a network of hamlets in the fertile Abibe mountains south of the lowland region of Urabá. SJA pioneered this concept of neutrality, a survival strategy to prevent being displaced from their land, yet again.

Like most PBI volunteers arriving in SJA for the first time after a bumpy two-hour uphill ride on a multi-coloured chiva, I was staggered by the sheer physical beauty of the mountains, rivers, vegetation - such fertile land. Then, over time, I was overwhelmed by the stories of the Community’s struggle: the suffering, grief, steadfastness, in the midst of historic butchery. And, finally, I was mesmerized by the strength of their collective identity, generosity, solidarity, humanity, and communal work ethic. Inspired by the politically conscious and organized resistance of SJA, many of us Brigadistas dreamed of putting our feelings into a great novel, short stories, epic poem, or famous academic tome. But to my knowledge, except for articles in Sunday colour supplements or dry ngo-type reports, none of us did. Until now, until Gwen did it!

Gwen Burnyeat spent two years with Peace Brigades in the Urabá region, much of it in SJA. She stayed on in Colombia to do a Masters in social anthropology at the National University in Bogotá, with the SJA Peace Community as her original research project.

As a participant observer in the cacao groves, Gwen picked up on what a powerful symbol cacao is for the Community. As a physical and intellectual product, it provides their cash crop, and their political and economic identity. Focusing her research on cacao production brings a certain distance. She could avoid arguing for or against the Community’s beliefs and concentrate on explaining how the Community sees itself, and why. Cacao sustains their two main narratives: the Radical and the Organic.

To understand the radicalisation of the SJA campesinos, we have to go back to their socio-political history in which the cacao tree looms large. As Gwen points out, “SJA campesinos farmed cacao long before they were a ‘peace community’”. One of their radical antecedents was the Patriotic Union, a socialist-inclined political party which established farming cooperatives all over Urabá and favoured campesino development projects. In 1985, the SJA campesinos created a cacao cooperative called Balsamar. It flourished for ten years, then collapsed in 1996 when all its leaders were publicly killed; part of the annihilation of the Patriotic Union party across Colombia, in which more than 5000 party members died. The majority of SJA campesinos fled.

Cacao was the crop that allowed them to rebuild their economic life after this forced displacement. The subsistence crops they had left – corn, beans and cassava – died through neglect, or were destroyed by the army because they thought the guerrillas might eat them. Cacao, on the other hand, being a tree, continued to grow and produce fruit, they had resisted until 500 campesinos gradually returned. Cacao came to symbolize resistance.

Cacao saved SJA then, and as the main cash crop of the newly created Peace Community, where work was now collectivised for security reasons, it became central to the Community’s desire for autonomy. The radical nature of SJA was guided at this stage by a Jesuit priest, Father Javier Giraldo, and a Colombian NGO now called the Interfaith Justice and Peace Commission (CIJP), formed in 1988 to provide physical and legal accompaniment to victims of the armed conflict. Its members, as well as being steeped in Colombian human rights culture, were influenced by Liberation Theology. They passed this ideology on to the Peace Community which incorporated it into their project to establish an ‘alternative community’. In 2002, the Community felt they had come through a strong enough organizational process to justify relinquishing the ‘hands on’ accompaniment of CIJP, keeping the international advocacy-based accompaniment of Peace Brigades.

However, a member of CIJP’s SJA field team, Eduar Lancheros, stayed on in a personal capacity and was central to shaping the Community’s already considerable antipathy to the Colombian state into an “ethical repudiation of the illegitimacy of the state”. Since then, a series of atrocities, food-blockades, and legal injustices against the Peace Community, pushed it into it’s now famous pioneering ‘rupture’, that is, non-engagement with the Colombian armed forces and the justice system.

As I have said, Gwen does not say rupture is good or bad, but explains how every contact the Community has with the state deepens their political ‘them and us’ attitude.

This Radical narrative runs parallel to the Community’s Organic narrative, which is the way they perceive their relationship with their social and natural environments and which, building on the pre-existent inclination to cherish their land, is now centred on growing only organically certified cacao. The Organic narrative has four other core elements:

First, the importance of food sovereignty. Small farming communities all over the world know that if you can feed yourself, you’re independent, and less subject to coercion. But in the Peace Community’s case, the food blockades periodically imposed by armed actors made self-sustainability a survival strategy as well. Moreover, in purely farming terms, cacao is grown to buy goods they can’t make or eat, so the Community need to plant other food ‘friends’ beside the trees, both to replace the soil’s nutrients and increase the land’s productivity. ‘Friends’ include avocado, baby banana, cassava, limes, mango, sugar cane, etc.

The second element is the contrast with the inorganic. Most people who eat home-grown food are suspicious of processed food. But for the Community, inorganic food has a special resonance. It means ‘unclean’ not only in the sense of chemically fertilized but also of being grown in a corrupt society. This applies to industrial bananas where chemicals are used to fumigate the weed then, having zapped the soil, more chemicals are needed to make the banana plants grow.

’Unclean’ also refers to coca, a crop widely grown in Colombia. A recently-added Peace Community rule is ‘No to Coca’ because both their Radical and Organic narratives associate it with illicit trade, contamination, violence, and death. If armed actors (who control coca production in the area) cannot enter their land, nor can the coca plant itself.

The Community’s third core element is their perception of economic development. The campesinos who survived the collapse of Balsamar understood the ‘solidarity economics’ of cooperatives; they had been decision makers. They knew the difference between that and the capitalist model of resource extraction and worker exploitation, of which they had the perfect example in the banana plantations on the plains below. Workers in primary commodities (like bananas and cacao) receive the least return for their work. Wages in neighbouring plantations (mostly Multinational-owned) were rock-bottom, bordering on bonded labour; unions having been largely destroyed by paramilitary activity. Chiquita Brands were convicted in the US of financing the spread of para-militarism in Urabá.

Workers in industrially-produced cacao may well have similar problems. But small-scale organic producers like SJA have a different, even anthropomorphic relationship to their cacao trees. One Community member said that the campesinos, who returned to SJA after displacement in 1996, felt the cacao was: “waiting for its master”.

Gwen devotes two chapters to describing the technicalities and complexity of organic cacao production. I found it lyrical and truly moving. It also shows the importance of learning, training, passing on knowledge. Skills acquired by families in situ are then reflected in the close link Community members feel with their end product - chocolate. Gwen quotes one woman who, despite the tiring work, talks of the satisfaction, even “love”, she feels when consumers enjoy it: “exhausted but happy”.

The fourth core element is the importance of organization. Again, while the campesinos in the Balsamar Cooperative had already organized and taken collective decisions, the life and death situation under which the Peace Community was established called for a tighter structure with stricter rules. They were crucial to survival. One of the Internal Council’s first jobs was to post the rules at the entrance to SJA. Strict sanctions were imposed for breaking them.

Community work of a least a day a week was compulsory. Organizing was multi-faceted as it served many purposes: large working groups meant safety in numbers; big tasks (construction, repairs, sowing, harvesting) had to be shared; sharing consolidated the collective identity; equal distribution of work and resources promoted integration; and so on and so forth, it was self-fulfilling.

Organization was also needed to buy land in strategic places both to protect the Community’s access and to stop mining and oil exploration by Multinationals. The Community also needed to coordinate actions in ‘the war’, like retrieving corpses, freeing prisoners, alerting international networks. And as the Community grew there were other key areas to be organized: education, alternative energy, finding new markets for their products.

Despite the growth and consolidation of the Peace Community during the first decade of its existence, killings, disappearances, and stigmatization continued. The horrific murder in 2005 of Internal Council leader Luis Eduardo Guerra, his wife and small son, three other adults, a six year-old, and a baby, gave the Community further proof for the state wanted to exterminate them. The army was proved to be the perpetrator, the then President Álvaro Uribe publicly stigmatized the victims as guerrillas, and the state investigation was slow and flawed. The atrocity resulted in total rupture with the Colombia state.

SJA’s already existing support networks were activated and the Community’s notoriety grew. International human rights NGOs invited SJA leaders on speaking tours. During one in Portugal, in 2009, at an eco-event they met Lush, a UK cosmetics Multinational with an ‘alternative’, ‘ethical’, ‘fair trade’ profile.

Soon Lush was buying 50 tonnes of organic cacao a year without intermediaries, and paying for fair trade certificates, transport and storage facilities! More amazingly, they seemed to be offering something else…. solidarity, advocacy.

For the Peace Community, this was highly unusual, if not downright suspicious. Multinationals were the baddies in their ‘them and us’ view of the world, the economic equivalent of the Colombian state. After decades of delegitimization, could it be that Lush was actually ‘on their side’?

And so it was. The done deal has prospered to for almost ten years. Lush reinforced the Community’s pre-existing Organic narrative about autonomy, alternative-ness, protecting the environment, etc. And who better to promote the Lush ethical image than the world’s most famously castigated rural Peace Community? But the SJA effect went even further, it persuaded Lush to see the economic and political link via which their customers actually make a political contribution, they ‘accompany’ the Community, and raise aware through signing petitions etc. This was first for Lush, seen first in UK. In Lush, the SJA Community seems to have found the perfect mutually advantageous commercial soul-mate.

Gwen started her research about the time Lush appeared on the scene. Her study is not only a fine piece of sophisticated ethnographic research, but also an affectionate description of a rural community’s complex struggle to build peace to a conflict zone. The SJA Peace Community is famous both for its Colombian campesino determination to stay on its land at all costs – and there have been many costs – and its ability to adapt to changing conditions, and search for allies in the human rights world both inside Colombia and internationally. Because she looks specifically at cacao, an inanimate object, Gwen’s approach to SJA is able to be even-handed - somewhere between the eulogizing by the international human rights community (like me) and the Colombian state’s historic condemnation. I sincerely take my hat off to Gwen for this beautiful book, with admiration and a certain jealousy. She has done something us other PBI Brigadistas have only dreamt of.

Afterword

So, is the Community safe?

As well as the Lush deal, things looked up in other ways. Juan Manuel Santos replaced Uribe as president in 2010 and, unlike his predecessor, recognized the existence of an internal armed conflict and therefore International Humanitarian Law, in which victims of conflicts have legal status.

In 2013 Santos publically apologized to the Community for Uribe’s stigmatization, and recognized their “brave struggle for the rights of all Colombians, who despite having lived through the conflict in flesh and blood, have persisted in their purpose to achieve peace for the country”. Despite his personal apology, however, the Community was not impressed. They set out four points that needed to be met before it was accepted. Stalemate. The Community’s rupture with the state continues.

Meanwhile Santos had entered peace talks with the FARC and an end to the conflict was announced in 2016. Fighting officially stopped, but there has been a dramatic rise in the number of murdered HRDs, as new armed groups fill power vacuums left by the demobilized guerrillas.

The Community still feels threatened. The Peace Plan has not been consolidated. Moreover, SJA’s economic progress and relatively stable environment of the past few years could be jeopardized if ex-President Uribe’s candidate wins the forthcoming Colombian elections.

'Chocolate, Politics and Peace-Building: An Ethnography of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, Colombia' (Palgrave Macmillan 2018).

Ethnographic Documentary 'Chocolate of Peace': chocolateofpeace.com

Documental etnográfico 'Chocolate de Paz': chocolatedepaz.com