Jorge Luis Borges inherited the friendship of a man who, educated in Law, graduated alongside his father, the elder Señor Borges. Upon Macedonio’s death on the 10th February 1952, Borges described the very personal legacy this lawyer-writer-philosopher had on his early years as a writer.

"I imitated him, to the point of transcription, to the point of devoted and impassioned plagiarism. I felt: Macedonio is metaphysics, is literature. Whoever preceded him might shine in history, but they were all rough drafts of Macedonio, imperfect previous versions.

For a writer who persistently argued of the absence of an original work of art; the idea that all literature was in fact translation, and vice versa, this was quite a testimony. Even with this, it is still generally thought that Borges spent most of his career at great pains to hide Macedonio's influence. Experts believe many of the most fundamental concepts underpinning Borges's fiction come directly from Macedonio. These include the questioning of space and time and their continuity; the confusion of dreaming and wakefulness; the unreliability of memory and the importance of forgetfulness; the slipperiness of personal identity; the denial of originality and the emphasis on texts as being recyclings and translations of prior texts; and the questioning and commingling of the roles of author, reader, editor and commentator.

Knowing the extent Macedonio's influence, one would expect to now reams of a writer whose precedents were mere “rough drafts.” But as he left little behind in the way of published works, there is something of a mysterious aura surrounding his name.

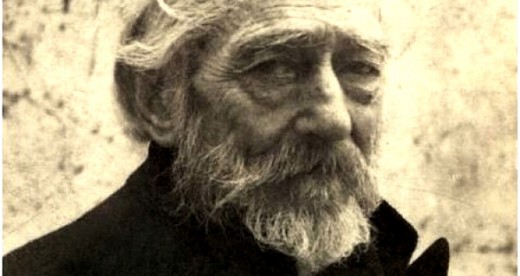

Search the Internet and you’ll discover wizard-like images of a man whose long silvery beard could rival that of Gandalf, coupled with tales of the stale alfajores* he stored in a suitcase under his bed. It is therefore not surprising that the most prominent biography on this enigmatic Argentine was given the title La Biografía Imposible (The Impossible Biography) by its author, Alvaro Abos. How then, are we to familiarise ourselves with this shadowy, but seemingly genius presence in the porteño literary canon?

A True Vanguard?

“At the forefront,” “leading the way,” “experimental,” and “new ideas”…the avant-garde is defined by its ability to break away from preconceived notions of how to produce a work of art. It has however been restricted to the educated bourgeoisie; after all, writing was often a luxury as opposed to a job that could sustain the individual. Macedonio Fernández was one of the “irregulars” of this world. He co-authored no manifesto, nor founded an -ism, instead his writings stand as a deep reflection of a personal philosophy – one in which art and life are poised as inseparable. This very personal manifesto echoes throughout, be it in the papers of a ‘newcomer’ (Papeles de recienvenido, 1944), in hair that acts as an extension of our thoughts, in a city that has flown away or in notebooks that at once detail ‘everything’ and ‘nothing’ (Cuadernos de todo y nada, 1972).

One of Macedonio’s most erratic, confusing but nevertheless poignant and witty texts was given the title, No toda es vigilia la de los ojos abiertos (Not everything is wakefulness when our eyes are open, 1928) - a refusal to accept wakefulness as merely the opening of the eyes.

The title is peppered with irony; it has the feel of an anecdotal warning and yet we are unsure who it is that is warning us - is Macedonio the author, the narrator or the character? As he plays between the literal and abstract, between seeing and knowing, between feeling and thinking, we are unsure whether we are reading fiction or philosophy. The text is fragmented, pages of an erratic thinker assembled together to form a labyrinthine mapping of one man’s mind, a mind that thinks without a library in a spontaneous way.

Life as a Sketch

Macedonio’s son Adolfo de Obieta wrote that his father described Not Everything is Wakefulnessas as a ‘borrador,’ a ‘sketch.’ This description of the work as a ‘sketch’ not only sums up Macedonio’s philosophy with regards to the politics of publishing and refusal to play the role of ‘author’, but is also suggestive of a ‘making’ process that has no end. Macedonio presents us with the ‘borrador’, this ‘sketch’ so that we might finish it, simply add to it or even rub it out and start again. A labyrinth is opened up, but we have to meet the writer part way; we are essentially a co-producer. Not Everything is Wakefulness brings together our notions literature and philosophy. This intertwining provokes questions, confusion and numerous paths from which to choose.

Borges is often attributed with having destabilised those systems that we assume stable; the ones on which we traditionally rely, such as our concept of time. His short stories propose a blend of fact and fiction; essay with poetry. Words twist and distort into the most unlikely images.

Macedonio claimed to write about ‘nada,’ and refused to adhere to traditional literary publishing processes, discarding papers and struggling to pay the bills in latter years. There are constant references to other genres, styles and even other artistic mediums. The result is a twisting labyrinth and it is the determined reader who has to put together the pieces to continue down the path. Flick through the pages of a work by Macedonio (translations are unfortunately notoriously difficult to get hold of) and you will notice an uncountable range of anecdotal philosophical gems such as, “There’s a world for each person born, and there’s nothing personal about not being born, it simply means not having a world”.

Nonsense? Macedonio goes on to say that he has never seen anyone, who, upon being born was found to be without a world of his or her own. Breaking it down, Macedonio seems to be saying that reality (or at least, what we deem ‘Reality’) is a dimension that we bring along when we our born, and consequently our notion of it, i.e. our ‘world,’ dies with us at the end of our lives.

Mmmmm….I’ll leave you to stew over that one.

Defining the undefineable?

Mexican writer Octavio Paz asked, “Why struggle to define the character of Spanish American literature? Literatures have no character. Or rather, contradiction, ambiguity, exception and hesitancy are traits which appear in all literatures. At the heart of every literature there is a continuous dialogue of oppositions, separations, bifurcations.”

Few writers and philosophers – whether Garcia Marquez’ ‘magical realism’ to Sartre’s ‘existentialism’ have been able to resist categorisation. Macedonio’s philosophical success is fame’s failure. Yet it leaves one free to pick up the great Argentine’s written thoughts, follow him down the trail of opposing, separating and bifurcating paths.

Rather than pretend to see and know it all with eyes open, we can be wakeful embracing and cherishing the mystery. If Macedonio left any kind of legacy, it was certainly one shrouded in lo misterioso. Perhaps his works were left in a state of incompleteness so that any reader, at any point in time, might sit up and take the reins even sixty years on…