Leaving the hospital, after seeing my mother battling against a cancer that can’t be cured, I saw a family pass by; a father, a mother, two kids and various others.

Beside the man, a youngster was walking, his head down, with an air of regret. He was the cause of a discussion, which we were invited into, as the old man cried:

“Even if you’re a thief and you’re in the wrong, it’s our duty to help you. And however many drugs you take, and however much you abuse us, we have to look after you. When you have children, you’ll understand that the duties of a parent never end, that the love of a mother and father never tires, that we want for you what we never had, that despite all our problems, family is family and love is love.”

As I saw this family move away with their tears, walking together, into a labyrinth of better and worse, I thought about my family, whom I loved so much in that moment, that my feelings overwhelmed me…

This is a scene I have imagined so many times I almost believe I have seen it myself. It is the story of my family, your family…a family in Panama, in London or anywhere in the world. And yet it is just a dance track.

There are many great Salsa tunes; ones that, when you hear them in a club and you’re dancing, you don’t want them to end. But when you hear this Salsa tune you find yourself almost…as the song itself goes, drowning in feeling. You want to cry, you want to embrace the person you love, tell them that you love them and, in the end, as its tempo quickens into a crescendo of optimism, you want to dance and celebrate life. This is the Rubén Blades effect.

This 1992 song and album of the same name, Amor y Control (Love and Control), are not Rubén Blades most famous. By the time it was released, Blades had already had a major impact on Salsa sales for the New York-based Fania label with Siembra (1978) - the best selling Salsa album for almost 20 years (until Marc Anthony’s Contra el Corriente in 1997). His 1984 album Buscando America (Looking for America) with words translated into English for the first time, had made him a world-wide artist, whilst the lyrics reflecting the struggles against the dictatorships sweeping Latin America, earned him the adoration of millions.

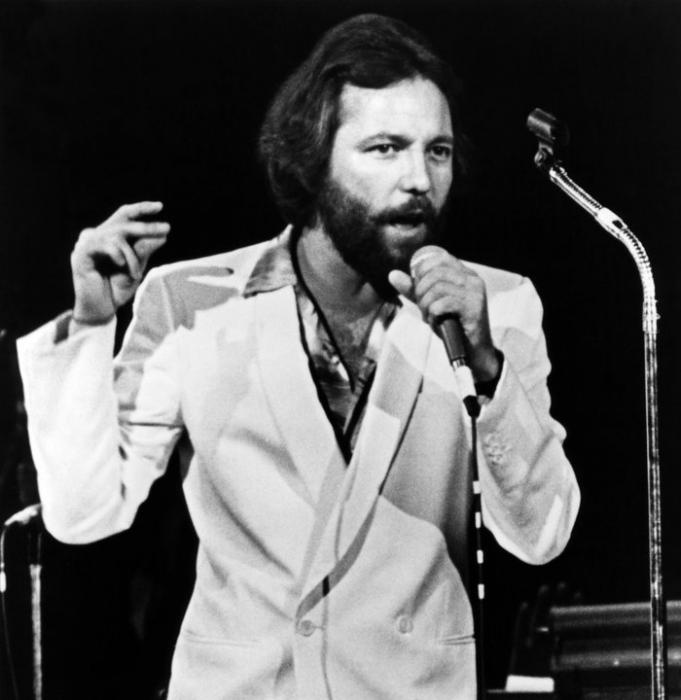

Yet Amor y Control marked a huge leap in defining Rubén Blades as a complete artist – the composer, the singer, the lyricist, the narrator, the poet, the social conscience, the political activist, all rolled into one – which set him apart from every other Salsa artist and eventually earned him the legendary status he has today.

A Salsero beyond his genre

Born in Panama to a Cuban mother and a father of English descent (hence the name), Blades was of a notably more middle class and whiter heritage than many of his Salsa peers from New York and Puerto Rico. Two important things, Blades says, marked his upbringing.

One was Panama’s musically, culturally and ethnically mixed environment; the Panama Canal had brought labourers and engineers from all over the world - the West Indies, Europe and Asia - and the country’s radio music reflected this diversity. Blades describes how, with few commercial constraints, radio deejays played pretty much anything they felt like:

“Cuban music was really popular, I remember listening to Beny Moré, Orchestra Aragón and La Sonora Macanzera. Colombia had its output of Vallenatos and Cumbias which were really influential too.” Because of the big American presence, people also had quick access to the latest US music. “We were very connected to what was going on. I remember hearing Bill Haley and the Comets, Frankie Lymon, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, The Platters and Frank Sinatra.”

However, with the US influence in Panama came the second big influence on Blades: political awareness.

“A big moment in my political awakening was the riots of January 9, (1964, when the US Army was involved in killing 22 Panamanians during protests). I was 16 and the incident was instrumental in spurring Panama to defend its sovereignty and the US’ eventual transfer of power over the Canal Zone to Panama.” Says Blades. “But my first inspirations in terms of political music were the Brazilians: Theo de Barros’ Terra de Ningem, Chico Buarque, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil.” The latter were all imprisoned by the dictatorship in Brazil because of their lyrics and forced into exile.

The other defining factor was the Blades family’s great emphasis on education: “I was always taught that I could do anything I wanted to.” Allegedly, Blades’ mother was so intent on him finishing Law School, at one point she virtually banned him from playing during Carnival, and Blades had to take down the banners advertising his performances on her driving route, and put them up again every day.

Nevertheless, the gifted Panamanian was already composing and making a name for himself beyond the country’s borders. It was Salsa’s golden era and during Carnival season the big Fania stars would come down from New York to perform in Panama. Blades claims it was Richie Ray, Bobby Cruz and Roberto Roena who first spotted him and went back to New York singing his praises.

In 1973, just as Rubén was graduating from Law School, the Blades family was exiled to Miami because of his father’s problems with the military regime. Figuring that he wasn’t going to be a lawyer in a country whose government had no respect for the law, Blades joined them.

A Latin American rebel in New York

Fania boss Jerry Masucci’s offer of a menial job in his mail room was enough to persuade Rubén to leave his parents’ home in Miami for New York. While the largely Puerto Rican artists at Fania’s epicentre, such as Willie Colón and Hector Lavoe, were singing about girls, heartbreaks, and having fun, Blades sung about a different Latin American experience of people living under dictatorships sweeping Latin America. His lyrics tapped into deeper truths and emotions than Salsa ever had, but Masucci was sceptical.

“At the time, my songs were considered too political, too literate, too long and too ‘anti-Salsa’. They confronted and documented the reality in our cities instead of merely promoting escapism, frivolity and clichéd imagery,” remembers Blades, who says, “it was Willie Colón who presented me with the opportunity to record the material I had written. He showed an intelligence and an understanding of Pan-Americanism which was absent from (Masucci’s) commercial notion of how to create a successful Salsa album.”

Colón and Blades went on to have some very public differences later on, Blades says he will always be grateful to Colón for that. “My first album came at a time when there were fourteen military dictatorships in Latin America. Juan Gonzalez (about a guerrilla fighter) was an anathema for radio stations.” However, Blades-Colón, the Lennon-McCartney of Salsa, proved the sceptics wrong, when Blades’ six-minute musical narrative of a low-life crook Pedro Navaja became an instant hit all over Latin America.

“When we arrived in places like Venezuela it was just...it was something else,” remembered Blades in a 1998 interview. “In New York, I don't think people understood what we were doing. But outside of New York City, we were kings. We had something to say. Whenever we played, people didn't just dance, they listened.”

An Inspiration for a generation

There’s a saying in Latin America: life and death dance together with a beer in hand. And people's hips would sway even while listening to Pablo Pueblo, about the down trodden common man, betrayed by politicians who buy votes with promises they never keep, or Plastico, about the shallow Miami-loving Latin American elites (‘you see their faces but never their hearts’) or Padre Antonio, the real life story of a left-wing priest who was brutally assassinated by El Salvador’s CIA-backed military government whilst he was performing mass.

Everyone has their favourite Rubén Blades. Tego Calderón, Puerto Rico’s godfather of Reggaetón told LatinoLife: ‘When Tiburón (Shark) came out, it was like a calling, it changed my life. There were other Salseros, but they never talked about the things Rubén Blades talked about. My father paid a lot of attention to his lyrics and that album was very important here, especially to the people of the Puerto Rican independence movement.

…The moon lies cushioned in the silence

Of the great resting Caribbean

Only the shark stays awake

Only the shark keeps searching

Only the shark remains restless

Only the shark watches your every move

‘Hmmmm, what a nice little flag

Shark, if yours is another sea

What are you doing here?

For London’s leading Latin DJ, Venezuelan born Jose Luis, it is Adán Garcia “…a family guy, struggling to make ends meet, and when his wife says she wants to borrow money from her parents, it’s like the last straw and he cracks up. He tries to rob a bank, is killed by police who then find he was carrying one of his kids’ plastic guns. Who couldn’t empathise with that? It’s a working man’s tragedy that could happen in Caracas or in Sheffield.”

Into the Nineties and the 21st century, albums such as Tiempos broke ground again, this time musically, by transcending the Salsa genre even further with more experimental compositions and showing off the ingenuity of his melodies and arrangements. Most importantly, Blades has had a major influence on the next generation, cited by some of the biggest names in Latin Music today, from Residente, who recorded a big hit with him, to Tego Calderón.

“Together with Ismael Rivera and Bob Marley, Blades is the artist that has most inspired me,” continues Tego “He made me realise: ‘this is what I want to do. I want to express myself. I want to talk about the reality I see.’”

Blades seems keenly aware of his influence: “I’m not played on the radio, I haven’t had a hit for years,“ he confesses frankly. “But my songs still inspire people and find new audiences. Why? I don’t know but I see thousands of young people at our shows singing songs that were written and recorded years before they were born. I guess the lyrics continue to be representative not just of Latin American barrios but of urban realities worldwide”

“Can music really change things? What advice would you give to young artists who seek this?” I ask:

“Sure music can create change. Mercedes Sosa, Victor Jara, Ali Primera, Caetano Veloso, Violeta Parra…all their countries ended up having Leftist governments, you don't think they played a role? And yes there are some artists doing this now, Residente springs to mind. What advice would I give? Write the truth as you understand it to be and, more importantly, embrace the Greek principle of Parrehsia as an artistic model. That is, the obligation to speak the truth for the common good, even at personal risk.”

From Rebel-Rousing to Politics

True to Masucci's fears, Rubén Blades began playing out his own discourse of the downtrodden man as he became more and more outspoken about the exploitation he witnessed at Fania. “There are no two ways about it,” Blades said at the time, “Jerry created opportunities for Salsa artists, but he ended up keeping their money. Every time one of them died, we had to pass the hat around to try to see how we could bury this person.”

Today Blades says it still upsets him: “we were exploited by labels who did not pay us what was ours and did not respect our work. I'm probably the only one at Fania who got something back, because I sued them, and I got my music, my publishing rights. But to this day, labels continue to own our masters, even after we’ve paid for them with our royalties.”

After leaving Fania and going on to have enormous success, Blades decided to enter politics for real. He ran for President of Panama and managed to get 15% of the vote, and has dabbled in film (resulting in an astounding thirty seven movies) with rather mixed results, it has to be said. One can debate the success of Blades’ diversions. True to the characters in his songs, he too has his contradictions, his ego, his flaws. Finally Blades went from outsider to the inner sanctums of government when he became Panama’s Minister of Tourism. One could see him in interviews, rather uncomfortably it seemed at times, talking about the security that tourists will find in Panama should they visit.

Have age and the experience of working in government changed your politics?

“I came out of the experience a less selfish person than when I went in. I discovered that positive social change can be introduced through government action and that people respond when there is a credible voice and project. It renewed my optimism in changing the world for the better. We can do it provided we stop acting like fingers and instead become hands.”

I suggest that the Left had its chance in Latin America and nothing much changed…Blades disagrees:

“Actually it’s only the Left that has given us the minimum wage, free education, workers rights, paid vacations. These benefits have never been given by Right-wing governments. The failure of Leftist governments reflects the failure of their leaders, not the failure of the Left’s values. Corruption is not limited to the Right; it’s a human failing. Does the pederasty among priests mean that Christ was wrong?”

If you were to write a sequel to Buscando America, what would the title be and what would it say?

“I would repeat the title. We have not found the real America yet; the one that it can and needs to be. And I still value the ideals of the songs I wrote back then.”

Older and chubbier, Blades’ rebel spirit hasn’t waned, as one recent Spanish interviewer learned when he referred to him as the Bruce Springsteen of South America. “I think what you mean…” Blades replied,”...is that Bruce Springsteen is the Rubén Blades of North America.” What other answer would you expect from The People’s Salsero?