Until now, Mark Bowden’s Killing Pablo, a North American author who also penned Black Hawk Down, has been the authoritative guide to the life and demise of Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar. The intriguing 2001 biography of how the small-time car thief from Medellín became a millionaire criminal capable of bringing his government to its knees has predictably gone the same way as Black Hawk Down — a Hollywood version starring Christian Bale is set for release in 2011.

Responsible for years of bloodshed between rival cartels and the kidnapping and killing of dozens politicians and journalists (Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla and Luis Carlos Galán, presidential candidate on the verge of election, were just two of his victims), at one time Escobar was said to be responsible for 80 percent of the cocaine entering the US. Thousands of people died due to the lucrative-beyond-your-wildest-dreams turf war while 10 percent of Colombia’s population remains displaced.

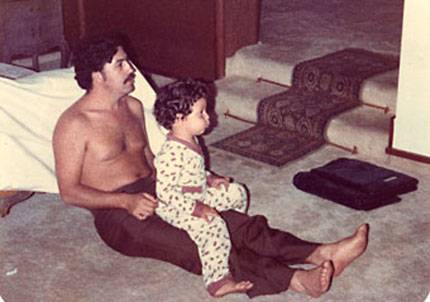

But until now, a word has never been publically uttered about Escobar by the people closest to him: his family. Following his 1993 death after a prolonged effort from the Colombian military, US special forces and death squad Los Pepes, Victoria Henao Vallejos, Juan Pablo Escobar and Manuela Escobar, respectively the drug baron’s wife, son and daughter, fled the country.

To cut to the end, the family moved to Mozambique but ended up in Argentina. And 16 years on, after countless proposals, Escobar’s son has finally agreed to share his memories inPecados de mi padres (Sins of My Father), a documentary by Argentine director Nicolás Entel, in the hope of ending the violence in Colombia.

Preferring to be interviewed in Spanish as “we are talking about very delicate subject matter and I might not be able to communicate the correct message if I don’t do it in my language,” Sebastián Marroquín, as Juan Pablo is now known, is polite, calm and maintains eye contact throughout.

RIGHT HERE, RIGHT NOW.

Saying that “everybody thought it logical I would become ‘Escobar 2.0’,” Sebastián is now an architect, married and based in Palermo. But why has he chosen now to speak out?

“I’ve rejected lots of money-making projects because they glorified the gangster style and image of my father. I never agreed with that idea because it seemed the opposite message to the lifestyle that I’ve chosen to lead. So I’ve always said ‘no’ to those kinds of proposals.

“But Nicolás suggested telling the story from the children’s point of view, not just mine, so as to integrate everybody else’s point of view. And that’s when I thought this story could have an interesting turn.”

By the children, he is referring to Rodrigo Lara Restrepo and the Galán brothers, Juan Manuel, Carlos and Claudio, sons of the murdered politicians who meet Sebastián for the first time in Pecados.

“Nicolás in fact called me a year before and I said’ no’. I’ve never hidden what has happened to me from anyone, but I realised this would give a vision to other families who have suffered at the hands of violence. But I think everything happens for a reason with specific synchrony.

“So I wanted to tell the story but not more of the same in which they simply tell the story and don’t leave you with a message. I always wanted to find another way of telling it — not so I was putting my father on a pedestal — but so we become aware of it so it doesn’t happen again.

“We were still exposed when we changed our identity and residency and when your secret place is no longer secret, and neither is your name, that led me to realise that there is nothing left to hide. The only thing that remained was to advance and share with the next generation what has happened.”

Sebastián has returned twice to Colombia: once to meet the Galán brothers and second, for the premiere. He left his homeland aged 16 and although he doesn’t sound obviously Colombian, he also has no distinctive Argentine accent either.

“I spent half my life in Colombia as Juan Pablo and the other half here as Sebastián so I feel I’ve learnt from both places and I feel part of both. I miss Colombia. It has changed for the better and has more hope than before, in terms of its security, economy and healthcare. Which is why I miss it even more. But I think I can be more useful for Colombia by being outside of the country. I’d like to return, when I’m older. But it isn’t possible for the moment, and I don’t think it’s prudent, either.”

CHANGES

After such upheaval from a young age, including the adoption of a new identity, surely documenting his current life means his life will change again following the international release ofPecados?

He says simply: “It already has changed. With respect to my names. But there is nothing else to hide which gives us the peace of mind to do a project, to share it. They’ve already discovered who we are here, they’ve investigated us for the past 13 years, and there is nothing more to hide so the only thing to do is move on and share this story.”

But putting himself in the spotlight after all this time still seems contradictory. Why do it? “For several reasons. I’ve learnt a lot of lessons from the worlds of violence and drug trafficking. And I chose not to continue down those paths. Not because I’m afraid or fear the law but because I have an intimate and human conviction that to enter those games is not the right thing to do. That’s what the violence I’ve suffered has taught me. I feel I have a social and moral task to return the message that life has taught me.

“Turn on the TV and you’ll see programmes that allude to the cartels and they show everything through rose-tinted spectacles. Beautiful girls, cars, mansions, money. It’s all wonderful. That’s the height of being a drug dealer. The suffering and death comes after that if you’re successful. So it’s important to me to show the opposite to what everybody thinks, the glamour, and all that.

“Kids enter the game as if nothing has ever happened before and I can see generation after generation clashing, and we’re in the same situation. I want the violence to stop, not just for me but for Colombia.

“There is also the necessity to ask for forgiveness for my father’s actions. They aren’t mine but I have to say to you that society has persecuted and punished us as if we were Pablo Escobar. The film allows a minute’s silence to hear our voices and to say ‘this is our story, this is how we live, please understand that to be someone’s son doesn’t mean they are also an accomplice’.

“The documentary is a way for us to send this message to society that they separate us as individuals and not as cartel members. We are members of the boss’ family, but we aren’t the cartel.”

MOVING ON.

Following 16 years as Juan Pablo and another 16 as Sebastián, is this a new stage for him? “I don’t even know who I am!” he laughs. “We don’t know where we’re going! But does anyone really know? I think it’s important to live with both sides of the story, the negative and positive from the first part of my life and apply that experience on a daily basis. I’m going to continue working and making money in the correct way without hurting anyone and this new life gives the opportunity of a profession here in Argentina with this identity. I have to live with this mixture. I’ll never be able to escape from my past, nor from my father, but if I can transform the present and also the future, well…

“I am trying to transform the reality that everybody thought it logical I would be come ‘Escobar 2.0’. Everybody expected that. Even me. But I realised in time, what we could do meant we could invite Colombians to understand that violence must not be generated. ‘Someone killed your dad, so when you’re older you go and kill someone else’s dad.’ The circle never ends.

“What takes places in the documentary is important. The children, we sit down, important characters in Colombia’s life, to end the violence. Let’s take a new path, unexplored, but we talk about a new path in order to inspire others.”

Even though many people expected Sebastián to follow in his father’s footsteps, a moment of choice had to occur for the young man. “I never considered the possibility of abandoning my father. I would not allow that as a son, as it would be an unforgivable disloyalty for me. I wouldn’t be able to sleep today if I didn’t have the clear conscience of having been a loving and respectful son towards my father, despite everything he did to society. That is the test of family values.

“But I could never have produced that violence. In life I criticised him. But it wasn’t in my hands, aged 14, to tell my father, because the FBI, the CIA, not even all the police in Colombia, nor all of his enemies could stop him. But I used to fight with him about the violence going on in Colombia. However, he was full of excuses for justifying it. That he’d suffered at the hands of violence that justified to him what he was doing. The same circle…”

NEW DAWN.

Starting life anew didn’t come without its complications. Having lived briefly in Mozambique, a war-torn country which at that time didn’t have any food on supermarket shelves, according to Sebastián, they headed back to South America. Given a three-month tourist visa by Argentina, the family decided to stay here. “At that point , three months seemed like a lifetime to us,” he says.

But at least they would have had money on their side to help them start afresh? He says: “We came here with what any plane passenger can bring. We were a family of four travelling and brought everything we physically could plus US$40,000. And with that we started a new life.” Although he is now a Palermo-based architect who happened to be investigated for 13 years by the Argentine Supreme Court because of his family connections, Sebastián and his family also make a living from the rights to his father’s image.

Discussing the documentary, how did the relationship work out with Nicolás ? “Well I did say to him, ‘please don’t lie about my father’s story.’ I’m used to that happening. And I wanted it to be dedicated to telling the truth but I didn’t have any control over the editing. Of course, lots of information was left out. A 30-year story can’t be squeezed into 90 minutes — it’s impossible.

“But the idea was always to tell it from the children’s point of view. I haven’t just met with Rodrigo, Juan Manuel, Carlos and Claudio. I’ve met lots of people — before I filmed anything — to ask their forgiveness that nobody is ever going to know about, people who prefer to remain anonymous, and I haven’t excluded anybody. I haven’t just met victims of my father but also people who caused damage to my father, conversations in which I forgive but have also asked for forgiveness.”

You can also read this article on http://www.sorrelmw.com/pecados and http://www.buenosairesherald.com/BreakingNews/View/31372